[ad_1]

Today I begin a three part series exploring interest rates and inflation.

How does the Fed influence inflation? Is the recent easing of inflation due to Fed policy, or happening on its own? To what extent should we look just to the Fed to bring inflation under control going forward?

The standard story: The Fed raises the interest rate. Inflation is somewhat sticky. (Inflation is sticky. This is important later.) Thus the real interest rate also rises. The higher real interest rate softens the economy. And a softer economy slowly lowers inflation. The effect happens with “long and variables lags,” so a higher interest rate today lowers inflation only a year or so from now.

interest rate -> (lag) softer economy -> (lag) inflation declines

This is a natural heir to the view Milton Friedman propounded in his 1968 AEA presidential address, updated with interest rates in place of money growth. A good recent example is Christina and David Romer’s paper underlying her AEA presidential address, which concludes of current events that as a result of the Fed’s recent interest-rate increases, “one would expect substantial negative impacts on real GDP and inflation in 2023 and 2024.”

This story is passed around like well worn truth. However, we’ll see that it’s actually much less founded than you may think. Today, I’ll look at simple facts. In my next post, I’ll look at current empirical work, and we’ll find that support for the standard view is much weaker than you might think. Then, I’ll look at theory. We’ll find that contemporary theory (i.e. for the last 30 years) is strained to come up with anything like the standard view.

There is a bit of a fudge factor: Theory wants to measure real interest rates as interest rate less expected future inflation. But in the standard story expected inflation is pretty sticky, so interest rates relative to current inflation will do. You can squint at next year’s actual inflation too.

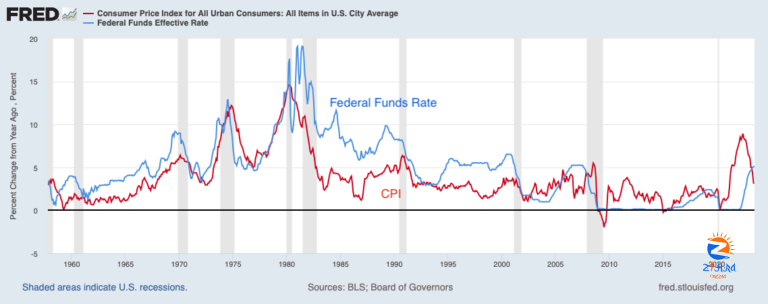

1980-1982 is the poster child for the standard view. Inflation peaked at 15%. Interest rates went to 20%, and for two years interest rates stayed above inflation and inflation declined. There was a severe recession too.

There weren’t visible “long and variable” lags, however. Inflation started going down right away. Eyeballing the graph, it looks pretty much like real interest rates push inflation down immediately, with no additional lagged effect. (One can find more of a lag from interest rate shocks, but then there is a question whether the shock has a lagged effect on the economy, or whether the higher interest rates that follow the shock affect the economy when they happen. Here we’re just looking at interest rates. I’ll come back to this issue next time discussing VARs.)

Is this a routine pattern or one data point? If one data point, it’s much more likely something else was involved in the 1980s disinflation (fiscal policy!) at least in addition to the standard story. The rest of the graph is not so comforting on this point.

In the standard story, the 1970s saw inflation spiral up because the Fed kept interest rates too low. Real interest rates are about zero throughout the 1970s. But the big story of the 1970s is the three waves of inflation – four if you count 1967. There is little in this pattern that suggests low real interest rates made inflation take off, or that high real interest rates brought inflation back down again. The interest rate line and inflation line are practically on top of each other. The standard story is told about the 1970s, waves of monetary stimulus and stringency, but it’s hard to see it in the actual data. (1970 conforms a bit if you add a one year long-and-variable lag.)

Now, you may say, those bouts of inflation were not due to Fed policy, they came from somewhere else. The standard story talks about “supply shocks” maybe, especially oil prices. (Fiscal shocks? : ) ) Perhaps the recessions also came from other forces. But that is a lot of my point — inflation can come from somewhere else, not just the Fed.

Moreover, the easing of inflation in the big waves of the 1970s did not involve noticeably high real interest rates.

It’s a historical precedent that ought to worry us now. Three times inflation came. Three times, inflation eased, with recessions but without large real interest rates. Three times inflation surged again, without obviously low real interest rates.

The correlation between real interest rates is also tenuous in the 1980s and beyond. Once inflation hit bottom in 1983, there is a decade of high interest rates with no additional inflation decline. Once again, you can cite other factors. Maybe strong supply side growth raises the “neutral” interest rate, so what counts as high or low changes over time? That’s why we do real empirical work. But it would be nicer if we could see things in the graph.

The 2001 recession and inflation drop is preceded by slightly higher interest rates. But also slightly higher inflation so there isn’t a big rise in real rates, and the real rates had been at the same level since the early 1990s. There is a little period of higher real interest rates before the 2008 recession, which you might connect to that recession and disinflation with a long and variable lag. But in both cases, we know that financial affairs precipitated the recessions, not high values of the overnight federal funds rate.

Then we have negative real interest rates in the 2010s, but inflation goes nowhere despite central banks explicit desire for more inflation. This looks like the 1980s in reverse. Again, maybe something else got in the way, but that’s my point today. Higher interest rates controlling inflation needs a lot of “something else,” because it doesn’t scream at you in the data.

Here, I add unemployment to the graph. The standard story has to go through weakening the economy, remember. Here you can see something of the old Phillips curve, if you squint hard. Higher unemployment is associated with declining inflation. But you can also see if you look again why the Phillips curve is elusive. In many cases, inflation goes down when unemployment is increasing, others when it is high. In most cases, especially recently, unemployment remains high long after inflation has settled down. So it’s a more tenuous mechanism than your eye will see. And, remember, we need both parts of the mechanism for the standard story. If unemployment drives inflation down, but higher interest rates don’t cause unemployment, then interest rates don’t affect inflation via the standard story.

That brings us to current events. Why did inflation start, and why is it easing? Will the Fed’s interest raises control inflation?

Inflation took off in February 2021. Yes, the real interest rate was slightly negative, but zero rates with slight inflation was the same pattern of recent recessions which did nothing to raise inflation. Unemployment, caused here clearly by the pandemic not by monetary policy, rose coincident with the decline in inflation, but was still somewhat high when inflation broke out, so a mechanism from low real rates to low unemployment to higher inflation does not work. Up until February 2021, the graph looks just like 2001 or 2008. Inflation came from somewhere else. (Fiscal policy, I think, but for our purposes today you can have supply shocks or greed.)

The Fed did not react, unusually. Compare this response to the 1970s. Even then, the Fed raised interest rates promptly with inflation. In 2021, while inflation was rising and the Fed did nothing, many people said the standard story was operating, with inflation spiraling away as a result of low (negative) real interest rates.

But then inflation stopped on its own and eased. The easing was coincident with the very few first interest rate rises. Only last April 2023 did the Federal funds rate finally exceed inflation. By the conventional story — 1980 — only now are real interest rates even positive, and able to have any effect. Yet inflation eased a full year earlier, with interest rates still far below inflation.

Moreover, unemployment was back to historic lows by 2022. Whatever the Fed is doing, it is manifestly not slowing the economy. Neither the high real interest rate, by conventional measure, nor the mechanism of softer economy is present to lower inflation. It’s really hard, via the standard story, to credit the Fed with the easing of inflation while interest rates were lower than inflation and unemployment below 4%. Though, certainly, in the standard story they were no longer making things worse.

Of course, now, analysts depart from the standard story. A lot of commentary now just ignores the fact that interest rates are below inflation. The Fed raised “interest rates,” we don’t talk about nominal vs. real, and proclaim this a great tightening. A bit more sophisticated analysis (including the Fed) posits that expected inflation is much lower than past inflation, so that real interest rates are much higher than the graph shows. Maybe by raising rates a little bit and giving speeches about its new philosophy, quietly abandoning flexible average inflation targeting, the Fed has re-established important credibility, so that these small interest rate rises have a big effect on expectations.

Indeed, there is lots of thinking these days that has the Fed act entirely through expectations. In the modern Phillips curve, we think of

inflation today = expected inflation next year + (coefficient) x unemployment (or output gap)

With this view, if speeches and signals can bring down expected inflation, then that helps current inflation. Indeed, most estimates pretty much give up on the last term, “coefficient” is close to zero, the Phillips curve is flat, unemployment goes up and down with very little change in inflation.

That has led many to think the Fed acts mainly through expectations. Speeches, forward guidance, “anchoring,” and so forth move the expected inflation term. There is a logical problem, of course: you can’t just talk, eventually you have to do something. If the coefficient is truly zero and the Fed’s actions have no effect on inflation, then speeches about expectations have eventually to be empty.

This is a quite different view than the “standard story” that we are looking at, though most commentators don’t recognize this and offer both the standard story and this Phillips curve at the same time. Theory post #3 will explore the difference between this current view of the Phillips curve and the standard story. Note that it really does say lower expected inflation or higher unemployment bring inflation down now. Now means now, not a year from now — that’s the expected inflation term. Higher unemployment brings down inflation now, and inflation is then less than expected inflation — higher unemployment makes inflation jump down and then rise over time. Post #3 will cover this sharp difference and the many efforts of modelers to make this modern Phillips curve produce something like the standard story, in which higher interest rates make inflation go down over time.

In sum, the standard story is that high interest rates soften the economy, with a lag, and that lowers inflation, also with a lag; and that interest rate policy is the main determinant of inflation so the Fed has main responsibility for controlling inflation. This story has not much changed since Milton Friedman in 1968, except with interest rates in place of money growth. 1980-1982 is the main episode interpreted that way. But it’s very hard to see this standard story by looking at the data in any other time period, and there are many periods that contradict the standard story. The modern Phillips curve tells a sharply different story.

So much for looking at graphs. We should look at real empirical work that controls for all those other forces. That’s the next post. We should look at theory more carefully, to see if the standard story survives all the changes in economics since Milton Friedman’s justly famous address and the similar ISLM models of the 1970s which still pervade policy thinking.

[ad_2]