[ad_1]

BENGALURU: The interpretation that the universe was expanding came after astronomers’ discovery in 1929 that galaxies are streaming away from us and each other. However, when they measured how fast it is expanding, they got different answers using different methods. The difference continues to be a thorn in their description of the expanding universe.

Now, a team of researchers led by Souvik Jana at the International Centre for Theoretical Sciences (ICTS), Bengaluru, have proposed a solution. Their paper, to be published in the Physical Review Letters, has been selected as an Editor’s suggestion.

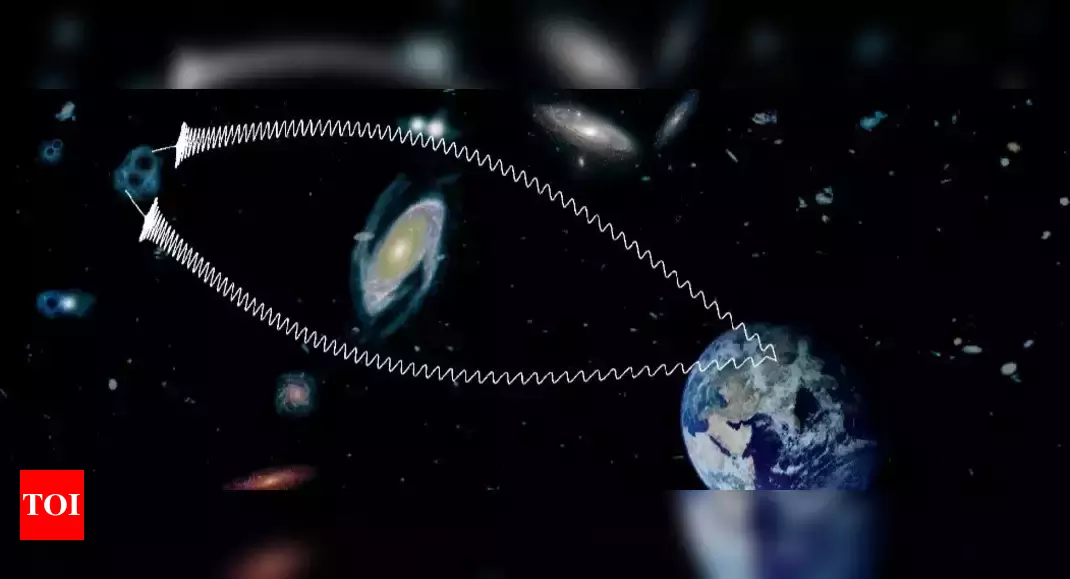

According to ICTS, the solution hinges on studying gravitational waves, ripples in spacetime, which astronomers first detected in 2015. The team studied how gravity itself affects gravitational waves.

“As pairs of black holes merge into a single black hole in a cosmic dance, they emit gravitational waves. As they reach Earth, kilometre-lengthed detectors help scientists study properties of the black hole pairs. Massive galaxies occupying space between the black holes and Earth change the paths of these spacetime ripples, resulting in detectors recording multiple copies of the same waves. Astronomers call this phenomenon gravitational lensing,” ICTS said.

Parameswaran Ajith, a co-author of the study said: “We have been observing the gravitational lensing of light for over a century. We expect the first observation of lensed gravitational waves in the next few years!”

In the next two decades, scientists will start running advanced gravitational wave detectors in search of the merging black holes. “Future detectors will be able to see out to much larger distances than the existing ones,” explained Shasvath J Kapadia, from the Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics (IUCAA) in Pune, one of the co-authors of the study.

Tejaswi Venumadhav from the University of California, another co-author, said they will be able to detect weaker gravitational wave signals that get buried in the noise affecting present detectors.

Astronomers estimate that advanced detectors will record signals from a few million black hole pairs, each merging to form a mega-black hole. Among these, about 10,000 black hole mergers will appear more than once in the same detector due to gravitational lensing.

The team led by Souvik demonstrated that by counting the number of such repeat black hole mergers and studying the delay between them, they can measure the universe’s expansion rate. As the data from advanced gravitational wave detectors trickle in over the next two decades, their method can potentially measure the universe’s expansion rate accurately.

The team’s proposal, Souvik said, does not require knowing properties of individual galaxies which create multiple copies of gravitational waves, the distances to the black hole pairs, or even their exact location in the sky.

Instead, it only requires an accurate method of knowing which signals are lensed. Scientists are improving their techniques to identify the repeat signals, Shasvath added.

“Gravitational lensing requires the astronomical source to be far away. The black hole pairs fit this criterion, which can originate a whooping 13.3 billion years ago, barely 500 million years old after the universe’s birth,” ICTS said.

Shasvath cautions that the proposed method will be helpful only when advanced detectors record millions of black hole mergers. Presently, the team is studying how such future observations will be able to tell apart different models of the universe.

The models, the team explained, attempt to solve mysteries of the elusive dark matter, a form of matter that does not interact with light. The dark matter hypothesis solves the astronomer’s problem of explaining why galaxies have the observed mass. However, scientists are still unsure of the dark matter’s properties, leading to various dark matter models.

The team’s ongoing research suggests that future observations of lensed gravitational waves will serve as a tool to study the properties of dark matter.

Now, a team of researchers led by Souvik Jana at the International Centre for Theoretical Sciences (ICTS), Bengaluru, have proposed a solution. Their paper, to be published in the Physical Review Letters, has been selected as an Editor’s suggestion.

According to ICTS, the solution hinges on studying gravitational waves, ripples in spacetime, which astronomers first detected in 2015. The team studied how gravity itself affects gravitational waves.

“As pairs of black holes merge into a single black hole in a cosmic dance, they emit gravitational waves. As they reach Earth, kilometre-lengthed detectors help scientists study properties of the black hole pairs. Massive galaxies occupying space between the black holes and Earth change the paths of these spacetime ripples, resulting in detectors recording multiple copies of the same waves. Astronomers call this phenomenon gravitational lensing,” ICTS said.

Parameswaran Ajith, a co-author of the study said: “We have been observing the gravitational lensing of light for over a century. We expect the first observation of lensed gravitational waves in the next few years!”

In the next two decades, scientists will start running advanced gravitational wave detectors in search of the merging black holes. “Future detectors will be able to see out to much larger distances than the existing ones,” explained Shasvath J Kapadia, from the Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics (IUCAA) in Pune, one of the co-authors of the study.

Tejaswi Venumadhav from the University of California, another co-author, said they will be able to detect weaker gravitational wave signals that get buried in the noise affecting present detectors.

Astronomers estimate that advanced detectors will record signals from a few million black hole pairs, each merging to form a mega-black hole. Among these, about 10,000 black hole mergers will appear more than once in the same detector due to gravitational lensing.

The team led by Souvik demonstrated that by counting the number of such repeat black hole mergers and studying the delay between them, they can measure the universe’s expansion rate. As the data from advanced gravitational wave detectors trickle in over the next two decades, their method can potentially measure the universe’s expansion rate accurately.

The team’s proposal, Souvik said, does not require knowing properties of individual galaxies which create multiple copies of gravitational waves, the distances to the black hole pairs, or even their exact location in the sky.

Instead, it only requires an accurate method of knowing which signals are lensed. Scientists are improving their techniques to identify the repeat signals, Shasvath added.

“Gravitational lensing requires the astronomical source to be far away. The black hole pairs fit this criterion, which can originate a whooping 13.3 billion years ago, barely 500 million years old after the universe’s birth,” ICTS said.

Shasvath cautions that the proposed method will be helpful only when advanced detectors record millions of black hole mergers. Presently, the team is studying how such future observations will be able to tell apart different models of the universe.

The models, the team explained, attempt to solve mysteries of the elusive dark matter, a form of matter that does not interact with light. The dark matter hypothesis solves the astronomer’s problem of explaining why galaxies have the observed mass. However, scientists are still unsure of the dark matter’s properties, leading to various dark matter models.

The team’s ongoing research suggests that future observations of lensed gravitational waves will serve as a tool to study the properties of dark matter.

[ad_2]