[ad_1]

But…all of this is slightly old data. How much worse will this get if the Fed raises interest rates a few more percentage points? A lot.

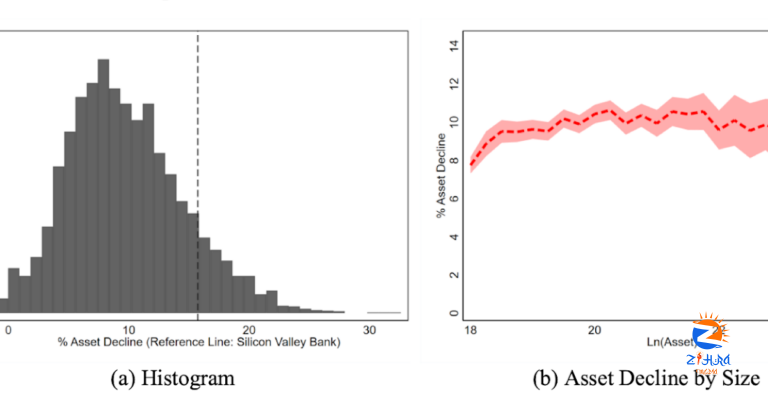

The median bank funds 9% of their assets with equity, 65% with insured deposits, and 26% with uninsured debt comprising uninsured deposits and other debt funding….SVB did stand out from other banks in its distribution of uninsured leverage, the ratio of uninsured debt to assets…SVB was in the 1st percentile of distribution in insured leverage. Over 78 percent of its assets was funded by uninsured deposits.

But it is not totally alone

the 95th percentile [most dangerous] bank uses 52 percent of uninsured debt. For this bank, even if only half of uninsured depositors panic, this leads to a withdrawal of one quarter of total marked to market value of the bank.

|

| Uninsured deposit to asset ratios calculated based on 2022Q1 balance sheets and mark-to-market values |

Overall, though,

…we consider whether the assets in the U.S. banking system are large enough to cover all uninsured deposits. Intuitively, this situation would arise if all uninsured deposits were to run, and the FDIC did not close the bank prior to the run ending. …virtually all banks (barring two) have enough assets to cover their uninsured deposit obligations. … there is little reason for uninsured depositors to run.

… SVB, is [was] one of the worst banks in this regard. Its marked-to-market assets are [were] barely enough to cover its uninsured deposits.

Breathe a temporary sigh of relief.

I am struck in the tables by the absence of wholesale funding. Banks used to get a lot of their money from repurchase agreements, commercial paper, and other uninsured and run-prone sources of funding. If that’s over, so much the better. But I may be misunderstanding the tables.

Summary: Banks were borrowing short and lending long, and not hedging their interest rate risk. As interest rates rise, bank asset values will fall. That has all sorts of ramifications. But for the moment, there is not a danger of a massive run. And the blanket guarantee on all deposits rules that out anyway.

Their bottom line:

There are several medium-run regulatory responses one can consider to an uninsured deposit crisis. One is to expand even more complex banking regulation on how banks account for mark to market losses. However, such rules and regulation, implemented by myriad of regulators with overlapping jurisdictions might not address the core issue at hand consistently

I love understated prose.

There does need to be retrospective. How are 100,000 pages of rules not enough to spot plain-vanilla duration risk — no complex derivatives here — combined with uninsured deposits? If four authors can do this in a weekend, how does the whole Fed and state regulators miss this in a year? (Ok, four really smart and hardworking authors, but still… )

Alternatively, banks could face stricter capital requirement… Discussions of this nature remind us of the heated debate that occurredafter the 2007 financial crisis, which many might argue did not result in sufficient progress on bank capital requirements…

My bottom line (again)

This debacle goes to prove that the whole architecture is hopeless: guarantee depositors and other creditors, regulators will make sure that banks don’t take too many risks. If they can’t see this, patching the ship again will not work.

If banks channeled all deposits into interest-paying reserves or short-term treasury debt, and financed all long-term lending with long-term liabilities, maturity-matched long-term debt and lots of equity, we would end private sector financial crises forever. Are the benefits of the current system worth it? (Plug for “towards a run-free financial system.” “Private sector” because a sovereign debt crisis is something else entirely.)

(A few other issues stand out in the SVB debacle. Apparently SVB did try to issue equity, but the run broke out before they could do so. Apparently, the Fed tried to find a buyer, but the anti-merger sentiments of the administration plus bad memories of how buyers were treated after 2008 stopped that. Beating up on mergers and buyers of bad banks has come back to haunt our regulators.)

Update:

(Thanks to Jonathan Parker) It looks like the methodology does not mark to market derivatives positions. (It would be hard to see how it could do so!) Thus a bank that protects itself with swap contracts would look worse than it actually is. (Translation: Banks can enter a contract that costs nothing, in which they pay a fixed rate of interest and receive a floating rate of interest. When interest rates go up, this contract makes a lot of money! )

Amit confirms,

As we say in our note, due to data limitations, we do not account for interest rate hedges across the banks. As far as we know SVB was not using such hedges…

Of course if they are, one has to ask who is the counterparty to such hedges and be sure they won’t similarly blow up. AIG comes to mind.

He adds:

note we don’t account for changes in credit risk on the asset side. All things equal this can make things worse for borrowers and their creditors with increases in interest rates. Think for a moment about real estate borrowers and pressures in sectors such as commercial real estate/offices etc. One could argue this number would be large.

So don’t sleep too well.

From an email correspondent:

Besides regulation, accountancy itself is a joke. KPMG Gave SVB, Signature Bank Clean Bill of Health Weeks Before Collapse.

How can unrealised losses near equal to a bank’s capital be ignored in the true and fair assessment of its financial condition (the core statement of an audit leaving out all the disclaimers) just because it was classified as Held to Maturity owing some nebulous past “intention” (whatever that was ever worth) not to sell?

It strikes me that both accounting and regulation have become so complicated that they blind intelligent people to obvious elephants in the room.

[ad_2]