[ad_1]

Subscribe

Apple | Google | Spotify | Amazon | Player.FM

Castbox | Stitcher | Podcast Republic | RSS | Patreon

Podcast Transcript

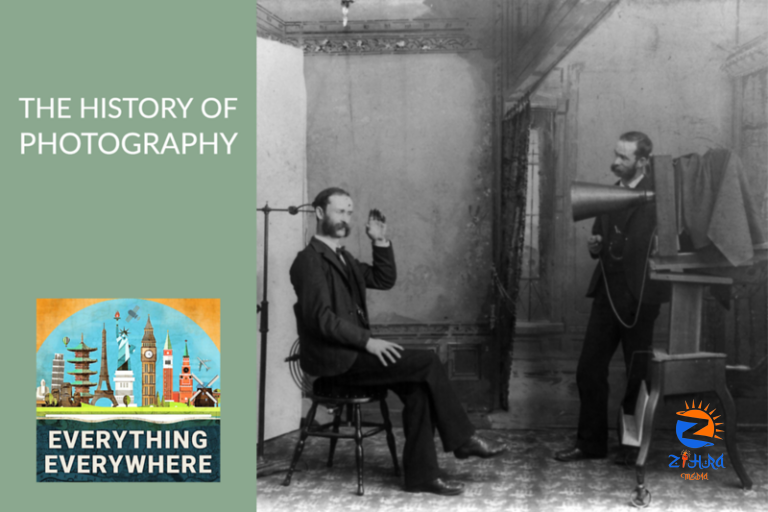

Prior to the 19th century, capturing images required the talent of an artist and a whole lot of time.

The transition from capturing images as an art to that of a science took multiple innovations and discoveries. Those innovations never really stopped as images went from being captured physically to being captured digitally.

Learn more about the history and evolution of cameras and photography, and how went from the first cameras to the camera in your smartphone, on this episode of Everything Everywhere Daily.

The development of the camera was sort of a chicken and egg thing. Both the camera and a light-sensitive photographic medium needed to be developed for either to make any sense.

Before these two things came together to create photography as we know it, they had independent paths of development. It was only when they were both at a point that was developed enough that we could have photography.

The development of the camera was really the development of optics. The earliest discovery of something camera-like would have been the camera obscura. I covered this briefly in my episode on Vermeer, but basically, a pinhole in a very dark room will project the image outside the pinhole into the room, upside down.

The earliest known documentation of the camera obscura effect was actually made in the 4th century BC in China.

Likewise, lenses in some form existed for centuries. Simple spectacles were made in the 13th century, but lenses and the art of lens grinding really came into their own in the 16th and 17th centuries. This is what allowed for the creation of telescopes and microscopes.

The other theoretical discovery that was necessary was Isaac Newton’s discovery that regular white light was actually made up of separate colors.

The camera obscura effect and the ability to bend light with lenses were obviously important, and the science of optics was developed first, but to make a photo light had to be able to imprint onto something to make the image permanent.

It had been known for centuries that certain silver compounds would darken when exposed to light. However, this was mostly just a curiosity. Moreover, no one really knew if it was light or heat which caused the change in color.

The 18th century saw more investigation into these photosensitive chemicals. The Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele discovered that silver chloride in particular was very sensitive to light.

This discovery was first used by the English inventor Thomas Wedgwood around 1790 to create the first proto-photos. He created what was called photograms. These were nothing more than images created without a camera by placing objects directly on top of photo-sensitive paper.

He would literally just put leaves and other objects on the paper, expose them to light, and that would then create an image with the shadows of what was put on top.

This idea was then taken to the next logical step by using a photosensitive material to make silhouettes of people.

The next real step was to put these things together. To use the camera obscura effect to shine light onto a photosensitive plate to record the image of what was coming through the pinhole.

This happened for the first time in 1825. The French inventor Nicéphore Niépce used a camera obscura to expose light onto a sheet of pewter covered in bitumen.

The world’s oldest known photograph was taken by Niépce in 1826. The photo is known as the “View from the Window at Le Gras”. It was an 8-hour exposure, and if you look at the photo, you can barely recognize it as a photo. However, if it is digitally enhanced, you can tell that it is roughly looking out a window with some buildings outside.

It wasn’t much, but it was a start.

Niépce called his system heliography and to be totally honest, it wasn’t very practical. Exposures took hours and the end product wasn’t very good.

The next big advance was by another French inventor, Louis Daguerre. He invented a system known as the Daguerreotype. Daguerreotype is both the name of the process and the name of the final image.

Daguerre introduced his process in 1839 and it was pretty much the photography system used over the next twenty years.

The process involved a silver-plated piece of copper which was highly polished to a mirror-like finish, and then exposed to halogen fumes to make it photosensitive, and it was later found that bromine exposure made it even more photosensitive.

After the exposure, the plat would be developed by exposing it to mercury fumes, which was really dangerous.

The original Daguerreotypes were not transferred to paper but were just displayed in their metal form.

The daguerreotype was eventually replaced by the emulsion plate or the wet plate. The main benefit of a wet plate is that it allowed for a much shorter exposure time, usually only as much as 2 or 3 seconds.

Wet plates were usually iron or glass. If you’ve seen photos from the American Civil War, they most probably were done on wet plates.

Wet plates were much simpler to use than daguerreotypes. This period also saw the use of cameras with bellows in the front which were used for focusing.

There were numerous, incremental advancements made to cameras including improved lenses and photographic plates. However, so long as plates were required, photography would still be something that was expensive and only for professionals.

The next big development came from a name you might recognize, George Eastman. In 1885, he developed a dry gel that could be applied to paper which could be used to expose images instead of a heavy plate.

In 1889, he moved from paper to celluloid to make the first photographic film. Here I’ll refer you to my episode on plastics, and the role of early celluloid. It was the development of film which allowed for the creation of motion pictures, which is another story.

In 1888, Eastman also introduced the world’s first commercial camera. He dubbed it “the Kodak”.

In 1901, they introduced what became a revolutionary camera that made photography for average people explode, the Kodak Brownie.

All the techniques I’ve mentioned so far produced black and white photos. Light exposure would darken the photosensitive material, but that was it.

The desire for color photos existed almost from the beginning, and the technique to create color photos was also known early on.

English physicist James Clerk Maxwell figured out that you just needed to take images with blue, red, and green filters and combine them to create a color image. The first color photo was taken with this method in 1861 by English inventor Thomas Sutton which is far earlier than most people suspect.

However, taking three different images with three different color filters was very difficult and time-consuming.

A simple method for color photography wasn’t developed until 1907 by Auguste and Louis Lumière, the same Lumiere Brothers who helped popularize moving pictures. Their system was called the autochrome plate.

Instead of three images, they created three layers of color filters on a single image plate. Each color would be exposed differently on each layer, and the end result would appear to be a color image.

Color photography was still quite rare and expensive until the development of the Kodak Kodachrome film in 1935. Kodachrome used a subtractive method of capturing color removing yellow, cyan, and magenta, rather than an additive system like the autochrome plates.

Kodak Kodachrome film was produced for an incredibly long time. The last rolls were discontinued in 2009.

I don’t want to imply that photography advancement stopped in 1935 because there were clearly continuous advancements in film, cameras, and lenses. However, photographic film fundamentals were pretty much the same for the next 75 years after Kodachrome was developed.

Formats changed, the form that film came in sometimes changed, but the basic chemical process didn’t radically change.

The next really big revolution in photography came from digital images.

The idea of digital images actually came quite soon after the development of digital computers.

Electronic images had obviously existed with televisions and with something called wirephotos, which was a method of sending images over telegraph lines.

In 1957, the first digital image was created when Russell Kirsch of the US National Institute of Standards and Technology did a wirephoto scan of a photo of his son. The resulting image was 176 by 176 pixels in size, and black and white.

While this was the first digital image, it wasn’t the first digital camera.

The ability to capture a digital image actually came about from the space program. As we sent probes to other planets, we couldn’t very well put film cameras on the probes as there was no way to recover the film.

The first interplanetary probes used modified television cameras, which captured an electric analog signal, similar to how televisions worked.

The big advance came with the development of the charged coupled device, or CCD.

A CCD is an array of capacitors that detects incoming photons. Each capacitor is called a pixel. As each pixel registers photons, it creates an electrical signal based on the wavelength and strength of light that hits the pixel.

The CCD was first developed in 1969 at Bell Labs and the work was later awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 2009.

CCDs are actually not used that much anymore for digital images. Newer image sensors called Active Pixel Sensors are used in modern smartphones, but the principle behind them is similar.

The CMOS or active pixel sensor was developed in 1993 by a team from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

CCDs are still found in very limited high-end applications where quality is an absolute must, like the cameras used on very large astronomical telescopes.

Digital cameras have gotten much better over time. The quality of images you can get from new smartphones is actually quite good. However, there will always be limits.

I’ve had people ask me if a smartphone camera is as good as a more expensive camera. The sensor on a smartphone camera is, given the form factor, very small. They have gotten better, but the fact remains that the light gathering area on such a sensor is always going to be small.

The size of a sensor in a proper digital camera is going to be larger, and each light-gathering pixel will be larger, thus gathering more light.

The number of pixels a sensor has is usually measured in megapixels. While some cameras can have an absurd number of megapixels, unless you happen to be printing very large images, anything more than about 10 or 12 is overkill. In fact, it can often make images lower in quality by reducing the size of each pixel on the physical sensor.

One thing I’m sure most of you are familiar with is digital file formats. The most popular format is jpeg. Jpeg stands for Joint Photographic Experts Group which established the format in 1992.

What it, and almost every other digital image format, does is compress the image so it has a smaller file size without dramatically diminishing quality.

The way it does this is by condensing similar pixels. For example, in an uncompressed image, details regarding the color for each pixel are given. So it might say, this pixel is black, this pixel is black, this pixel is black, and so on.

In a compressed image, it would just store that information as “Pixels 1 through 7 are all black”, which requires less space. Hence, the simpler an image is, the easier it is to compress.

Many new digital technologies haven’t totally replaced their previous analog predecessors. In photography, however, that is exactly what happened. Other than niche hobbyists, film has pretty much been totally replaced by digital photography.

This has ensured that even though the roots of photography go back almost 200 years, it is still an area where there is significant investment and innovation today.

Everything Everywhere Daily is an Airwave Media Podcast.

The executive producer is Darcy Adams.

The associate producers are Thor Thomsen and Peter Bennett.

Today’s review comes from listener Vern over at PodcastRepublic. He writes:

Always interesting, even if the title of the episode doesn’t seem like it will be an interesting one. An incredible wealth of knowledge packed into small, quick-to-listen to segments.

Thanks, Vern! You have discovered one of the secrets to the show. If you skip an episode because it doesn’t seem interesting, you might be skipping something interesting, but you just didn’t know it.

Remember, if you leave a review over at Podchaser until the end of April, they will make a donation to help feed Ukrainian refugees, which will be matched by several other podcast companies.

[ad_2]