[ad_1]

Vaccine makers including Pfizer Inc. and Moderna Inc., plus U.S. government and academic scientists, are rushing to run lab tests expected to yield answers. Most labs expect results in a few weeks, though a South African research institute said Tuesday early findings from lab tests showed the vaccine from Pfizer and BioNTech SE generated one-fortieth of the infection-fighting antibodies against the Omicron variant, compared with its performance against the original version of the virus.

The answers could help determine whether companies need to roll out modified booster shots that specifically target the Omicron variant, or if existing shots will suffice.

“If we get an early look in a couple of weeks, that’s a monumental effort,” said Dr. Kathleen Neuzil, director of the Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, who has helped conduct several studies of Covid-19 vaccines. “It’s still a scramble and a lot of work.”

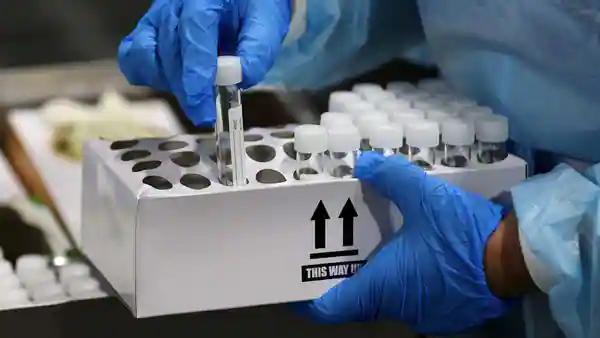

A critical part of the effort to assess vaccines is for scientists to gather the blood samples—specifically, serum, the portion of blood that remains after it has clotted—previously taken from people who received Covid-19 vaccines in clinical trials or from real-world use of the vaccines.

Most of the tens of thousands of people who enrolled in these studies starting last year gave blood samples before and after vaccination so that researchers could analyze changes in immune-system antibodies. Various clinical-trial sites, companies and government scientists have stored the samples.

Now scientists are using these same samples to run tests in petri-type dishes, and the samples are proving useful as new variants emerge, the latest being Omicron. “The fact that we have this bank of specimens is working in our favor,” Dr. Neuzil said.

“We’re looking rapidly to test sera from people who’ve been vaccinated with our vaccine, as every other manufacturer is,” Moderna President Stephen Hoge said at an investor conference Dec. 1.

Another key component of these tests: modified versions of the coronavirus, known as pseudoviruses. They are engineered to resemble a live Omicron virus but don’t replicate, so they are safer to handle in labs.

Researchers mix the blood samples with the Omicron pseudovirus in lab dishes and incubate them. They add cells from human cell lines—such as human kidney cells that are grown in batches in a lab for research purposes—to the mix, to see whether the pseudoviruses are able to get inside cells, or whether the vaccine-induced antibodies block them.

The pseudoviruses also contain an enzyme called luciferase, which is what makes fireflies glow, and which helps researchers track the antibodies’ effects on the pseudovirus.

The luciferase allows the researchers to visualize the virus and see whether it gets into cells. Machines called luminometers, which are the size of a desktop computer, measure the luminescence in the cells and quantify whether the pseudovirus is getting into cells, and how much, said Dan Barouch, director of the center for virology and vaccine research at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. His lab is running these tests on serums from people vaccinated with the Johnson & Johnson shot—which he helped design—as well as the shots from Pfizer and Moderna.

Some labs with the required biosafety precautions also are running live-virus tests with Omicron and blood samples, as with the South Africa research released Tuesday. But scientists have found that results of pseudovirus tests are usually consistent with those using live viruses.

The pseudoviruses include the genetic mutations found in the spike protein on the surface of the Omicron virus variant. The spike protein is the main target of the Covid-19 vaccines in triggering immune responses.

Most labs need to order from outside suppliers the synthetic genes with the coding for the Omicron spike protein, and then it takes several days to construct a pseudovirus, said John Mascola, director of the vaccine-research center at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The institute is also testing Covid-19 vaccines against Omicron.

The blood-sample test results are likely to predict how the vaccines hold up against Omicron, but they will have limitations, Dr. Mascola said.

Scientists also will assess other elements of the immune response induced by the vaccines, apart from antibody production, but those tests could take longer.

More definitive answers about the vaccines’ activity against Omicron will come later, when researchers observe how well vaccines are protecting against Omicron in vaccinated people, not lab dishes. They’ll be able to see whether vaccinated people are getting breakthrough infections or severe disease at higher rates than for other variants.

Norway officials said they have seen some cases of the Omicron variant in vaccinated people, but most have been overwhelmingly mild. Scientists, however, say it is too early to determine whether the level of disease severity reported is linked to age, prior infection, vaccination or some property of Omicron itself.

Health officials in South Africa identified the Omicron variant in late November, and it has since been detected in several other countries, including the U.S. The World Health Organization says the variant might increase the risk of reinfection compared with other variants. There have been early signals that Omicron is highly transmissible but may cause milder illness than initially feared; health authorities are still exploring these questions.

The Omicron variant has an unusually high number of mutations compared with previous strains, triggering concerns that it could escape immunity conferred by the vaccines. Most Covid-19 vaccines were designed to target the coronavirus strain that emerged in China and was predominant during 2020.

It is possible that the Covid-19 vaccines will be less effective at preventing Omicron infections, but would retain their effectiveness against severe disease caused by the virus, said William Moss, executive director of the International Vaccine Access Center at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. That could happen if vaccines induce insufficient immune-system antibodies against infection, but still mobilize the immune system’s “memory response” that limits infections from worsening, he said.

Vaccine makers and government officials relied partly on tests of blood samples earlier this year to conclude that the vaccines had reduced neutralizing activity against the highly transmissible Delta variant, but were still sufficient to provide protection against severe disease caused by that strain.

Never miss a story! Stay connected and informed with Mint.

Download

our App Now!!

[ad_2]