[ad_1]

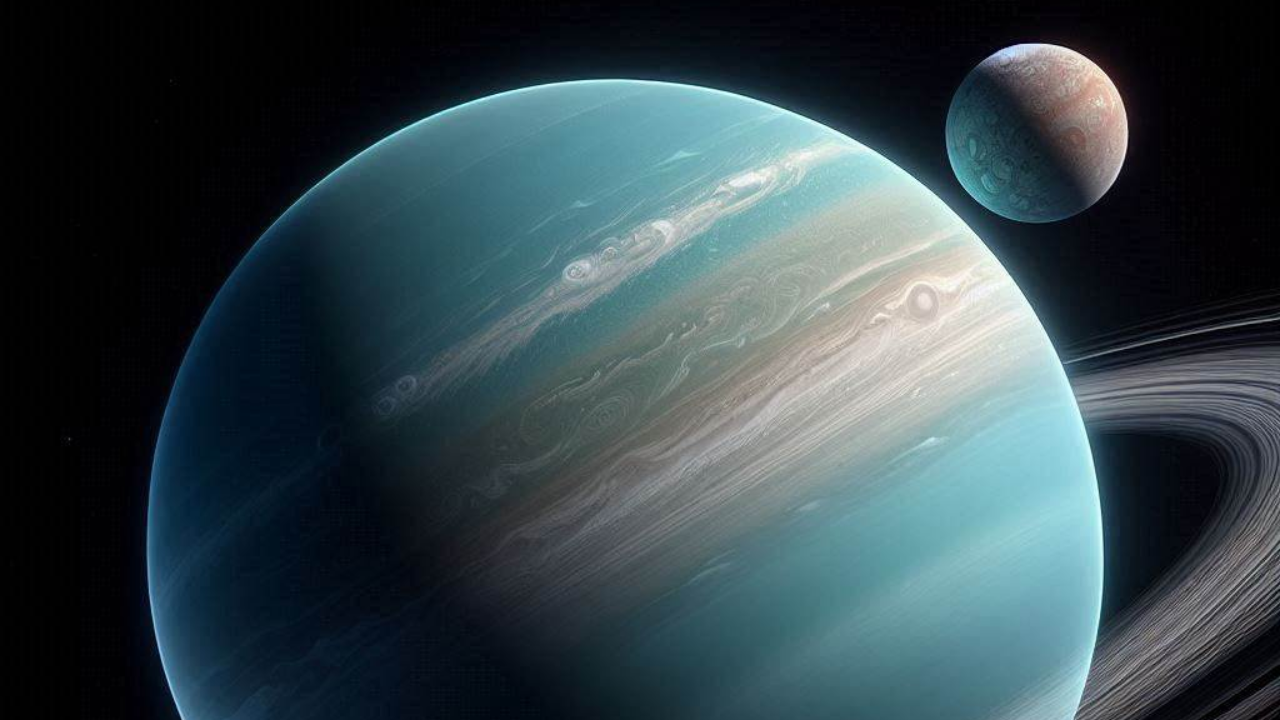

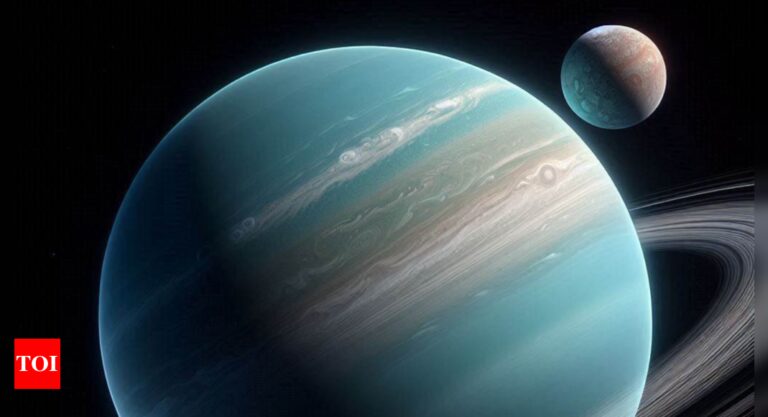

Using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), astronomers have made a remarkable discovery about Ariel, one of Uranus’ moons. The findings suggest that Ariel may harbour a hidden subsurface liquid water ocean, which could help explain the puzzling presence of significant amounts of carbon dioxide ice on its surface.

At Uranus’ distance from the sun, carbon dioxide typically exists as a gas and escapes into space.Previous theories proposed that the carbon dioxide on Ariel’s surface was replenished through radiolysis, a process involving interactions between the moon’s surface and charged particles trapped in Uranus’ magnetosphere, according to a report from Space.com.

However, the new evidence from JWST points to a different source: Ariel’s interior.

By analysing the spectra of light from Ariel using JWST, researchers discovered that the moon has some of the most carbon dioxide-rich deposits in the solar system. They also detected clear deposits of carbon monoxide for the first time, which should not be stable at Ariel’s average surface temperature of around 65 degrees Fahrenheit (18 degrees Celsius). This suggests that the carbon monoxide must be actively replenished, possibly from a liquid water ocean beneath Ariel’s icy shell.

The majority of the carbon oxides on Ariel’s surface could be created by chemical processes in this subsurface ocean and then escape through cracks in the icy shell or be ejected by powerful cryovolcanic plumes. The presence of carbonite minerals, which form when rock interacts with liquid water, further supports the idea of a subsurface ocean.

The findings highlight the need for a dedicated mission to the Uranian system, as emphasized by the Planetary Science and Astrobiology decadal survey in 2023. Such a mission could provide valuable information about Uranus, Neptune, and their potentially ocean-bearing moons, with implications for understanding extrasolar planets as well.

The team’s research, published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters on July 24, underscores the compelling nature of the Uranian system and the importance of future exploration to unlock its secrets.

At Uranus’ distance from the sun, carbon dioxide typically exists as a gas and escapes into space.Previous theories proposed that the carbon dioxide on Ariel’s surface was replenished through radiolysis, a process involving interactions between the moon’s surface and charged particles trapped in Uranus’ magnetosphere, according to a report from Space.com.

However, the new evidence from JWST points to a different source: Ariel’s interior.

By analysing the spectra of light from Ariel using JWST, researchers discovered that the moon has some of the most carbon dioxide-rich deposits in the solar system. They also detected clear deposits of carbon monoxide for the first time, which should not be stable at Ariel’s average surface temperature of around 65 degrees Fahrenheit (18 degrees Celsius). This suggests that the carbon monoxide must be actively replenished, possibly from a liquid water ocean beneath Ariel’s icy shell.

The majority of the carbon oxides on Ariel’s surface could be created by chemical processes in this subsurface ocean and then escape through cracks in the icy shell or be ejected by powerful cryovolcanic plumes. The presence of carbonite minerals, which form when rock interacts with liquid water, further supports the idea of a subsurface ocean.

The findings highlight the need for a dedicated mission to the Uranian system, as emphasized by the Planetary Science and Astrobiology decadal survey in 2023. Such a mission could provide valuable information about Uranus, Neptune, and their potentially ocean-bearing moons, with implications for understanding extrasolar planets as well.

The team’s research, published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters on July 24, underscores the compelling nature of the Uranian system and the importance of future exploration to unlock its secrets.

[ad_2]