[ad_1]

Subscribe

Apple | Spotify | Amazon | iHeart Radio | Player.FM | TuneIn

Castbox | Podurama | Podcast Republic | RSS | Patreon

Podcast Transcript

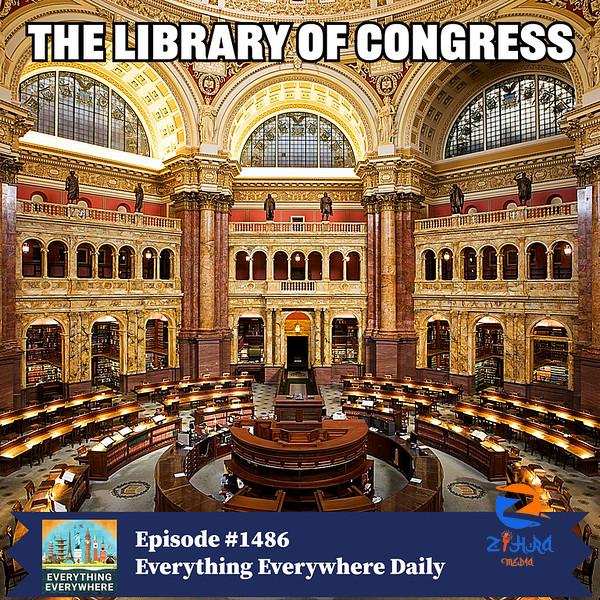

According to the Guinness Book of World Records, the largest library in the world is the Library of Congress in Washington, DC.

The Library of Congress was originally intended to be the library of the United States Congress, but over two centuries since its founding, it has evolved to something much grander, covering almost every subject and language imaginable.

Learn more about the Library of Congress, why it was established and how it works on this episode of Everything Everywhere Daily.

The Library of Congress is one of, or perhaps the largest library in the world. I will address the size of the current library relative to others in a bit.

While it is certainly a library, it is unlike any library you are familiar with. It isn’t your community lending library or a college research library; however, it does have some elements of both.

The story of how the Library of Congress came to be and how it became so big begins in 1783 with the American founding father, James Madison.

Madison was a member of the Congress of the Confederation, which was the legislature under the original Articles of Confederation after the American Revolution.

Madison made what seemed like a rather simple proposal. He proposed a library that contained books relevant to Congress so that they could do their job.

Madison’s proposal was not adopted, but the idea stuck around.

After the ratification of the US Constitution in 1788, the first congress sat in New York City. In 1790, the Residence Act was passed which established a new national capital at an undeveloped location along the banks of the Patomic River including what was parts of Maryalnd and Virgina.

Until the new capital was ready, Congress temporarily resided in Philadelphia.

When Congress was in New York and Philadelphia, it simply used the libraries in those cities. The Philadelphia Library Company and New York Society Library served as de facto libraries for Congress during that period. When Congress needed information, it just used the resources that were available to it, and there was no need in those early years for a dedicated library for Congress.

Benjamin Franklin established the Philadelphia Library Company in 1731, which was the first lending library in the United States.

The New York Society Library was established in 1754 and was an early subscription library, which required fees to be a member.

Both libraries still exist today and are amongst the oldest cultural institutions in each city.

In 1800, Congress was finally ready to move to its new capital, Washington. The problem was, they couldn’t use readily existing libraries like they did in new York and Philadelphia because there was nothing in Washington. Everything was being built from scratch.

On April 24, 1800, President John Adams signed an act of Congress providing for the official transfer of the seat of government from Philadelphia to Washington, D.C. This act allocated $5,000 for the purchase of books and the fitting up of a suitable apartment for their reception.

$5,000 doesn’t seem like a lot of money, but it was a lot of money back then. However, by the same token, books also cost a lot of money back then too.

The initial collection of the library consisted of 740 books and three maps. All of the books had to be ordered from London because there wasn’t yet a publishing industry in the country to rival that of the United Kingdom.

In 1801, Thomas Jefferson became president. Jefferson was a advocate of libraries and himself had a large personal collection of books.

In 1802, Jefferson signed into a law a resolution which provided some organization and structure for the congressional library.

General oversight of the library was to be given to a joint congressional committee consisting of members of the House and Senate, the first joint committee in congressional history.

The day-to-day administration of the library was to be assigned to a new position of the Librarian of Congress. Oddly enough, Congress didn’t have the power to confirm the appointment of the librarian until 1897.

The first Librarian of Congress was John J. Beckley. Beckley wasn’t a professional librarian. He was a political creature considered to be the first campaign manager in American history and played a fundamental role in the creation of Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican party.

Beckley was paid $2 per day, and a big part of his job was serving as a clerk for Congress. The position of Librarian of Congress was a lifetime appointment until 2015.

The 1802 law also extended lending privileges to the president and the vice president.

The important thing was that this early library was literally just a library for Congress and the executive branch.

The next big event in the history of the LIbrary of Congress took place in 1814. During the invasion of Washington by the British during the War of 1812, their commander George Cockburn ordered the burning of several government buildings, including the Library of Congress.

During the subsequent fire, most of the 3000 volumes held by the library were destroyed. One of the only titles that survived was titled “An Account of the Receipts and Expenditures of the United States for the year 1810.”

Cockburn took the book as a trophy and it was held in his family for almost 125 years until it was returned by the family in 1940.

With the library all but destroyed, it was Thomas Jefferson who came to the rescue.

Jefferson offered to sell his large personal library of 6,487 books to restart the Congressional library. Jefferson’s personal library was both larger and qualitatively different than the pre-1814 Congressional library.

He was 71 years old at the time of the offer, and he had spent over 50 years collecting a very eclectic mix of books on a wide variety of subjects from all over the world. His collection included things that normally would not be considered part of a legislative library.

His library had copies of the Koran, cookbooks, books on technology, science, mathematics, ancient civilizations, art, and many other subjects.

Jefferson felt that all subjects should be part of any library for Congress. He said

I do not know that it contains any branch of science which Congress would wish to exclude from their collection; there is, in fact, no subject to which a Member of Congress may not have occasion to refer.

In 1815, Congress agreed to buy the Jefferson collection for $23,950.

The library had now fundamentally changed. It was twice the size it was before the war, and it was now a general library, not a specialist library.

The library kept growing over the years with occasional requests for funding and new material.

The next major event in the library’s history was another fire in 1851. This fire destroyed 35,000 of the 52,000 books held by the library at the time, including most of the originals purchased in the Jefferson collection.

The next year, Congress approved $168,700 to replace the books that were lost, but not to buy anything new. Over 170 years since the fire, the library has managed to find replacements for all but 300 books.

During the 1850s, there was much debate about what the library should be. John Silva Meehan, the fourth Librarian of Congress, advocated for a limited scope. The Smithsonian Institute also lobbied to become the National Library, but the board eventually opted to focus on scientific research.

The library languished during the Civil War, but in 1864, President Abraham Lincoln made the most significant appointment in the history of the library, when he appointed Ainsworth Rand Spofford as the Librarian of Congress.

Spofford was the Chief Assistant Librarian of Congress under his predecessor, John Gould Stephenson, who spent most of his time as a medic during the war.

Spofford held the position for thirty-three years and saw a major expansion of the library during his tenure. He developed support from both sides of the aisle to turn the library into a true national library. He began collecting extensive volumes of American literature.

He was instrumental in advocating for and overseeing the construction of the Thomas Jefferson Building, which opened in 1897. This building was the first structure designed specifically to house the Library of Congress and was designed to be fireproof.

When the library moved there in 1897, it had a collection of 840,000 volumes.

Spofford’s successor, John Russell Young, only held the job for two years, but in that time, he introduced one of the biggest changes to the library: the Library of Congress Classification system.

Prior to this time, the library had been organized by Jefferson’s original personal system, which he adopted from Francis Bacon’s categorization of knowledge.

Young, a former diplomat, also greatly expanded the library’s collection of foreign volumes.

After Young, the position went to Herbert Putnam, who held it for forty years. Putnam expanded the library’s role beyond just a resource for Congress.

The Library of Congress became available for interlibrary loan to other major libraries. He also created the Legislative Reference Service, which was a service members of Congress could use to get research on almost any issue they might have. This was later renamed to the Congressional Research Service in 1970.

The library’s collection kept growing. It expanded beyond books to include musical instruments. The position of The Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress was established in 1937 and is more commonly known as the Poet Laureate of the United States.

In 1939, President Franklin Roosevelt appointed Archibald MacLeish as the Librarian of Congress, who became the most famous person ever to hold the position. He was a strong promoter of democracy during the war and was later appointed as Assistant Secretary of State.

The growth of the library’s collection throughout the 20th century was astounding.

It reached a million volumes in 1910, 5 million volumes in 1930, 10 million volumes in 1950, 20 million in 1970, and 90 million by 1990.

James Billington was appointed Librarian of Congress in 1987 and held the position until 2014. During his tenure, the number of volumes in the collection grew from 87 million to 160 million.

Under Billington’s leadership, he created the National Digital Library Program.

The National Digital Library Program is an initiative by the Library of Congress aimed at making a significant portion of its vast collections accessible online to the public. Launched in the 1990s, the program focuses on digitizing and preserving a wide range of historical and cultural materials, including manuscripts, maps, photographs, sound recordings, and films.

One of the functions of the Library of Congress is to run the United States Copyright Office.

By law, every publisher my submit two copies of all published works to the library of congress. This results in 15,000 items being sent to the Library of Congress every day. Of those about 12,000 are added to the collection.

The library attempts to collect every significant work that has been published in the English language from anywhere in the world.

Today, there are almost 175 million items in the collection, of which about 40 million are books.

There are 838 miles or 1,349 kilometers of shelving to hold everything.

The best current estimate I could find is that if all of the printed text in the Library of Congress were converted to digital data, it would take up about 15 terabytes. If that seems shocking, it is because of how little space text takes up. You can easily find 20 TB hard drives for sale for a few hundred dollars.

As of 2022, the Library managed 21 petabytes of digital collection content, comprising 914 million unique files.

If you think you are a digital packrat, you have nothing on the Library of Congress.

I want to end with something I mentioned at the start of the episode. What is the largest library in the world?

There are only two contenders for the title: The Library of Congress and the British Library.

The Guinness Book of World Records has declared the Library of Congress to be the largest. However, you will find some who say the British Library is.

The confusion comes from an incredibly wide range of estimates for the size of the British Library’s collection. I’ve seen estimates that go from 150 million to 200 million. The gap in estimates is larger than any other library in the world.

The Library of Congress has changed considerably since its inception. Its collection has grown exponentially over the years, and the scope of its services and items in its collection has changed. Yet, officially, its mission has never changed in almost 225 years: serving as a resource for the members of the United States Congress.

[ad_2]