[ad_1]

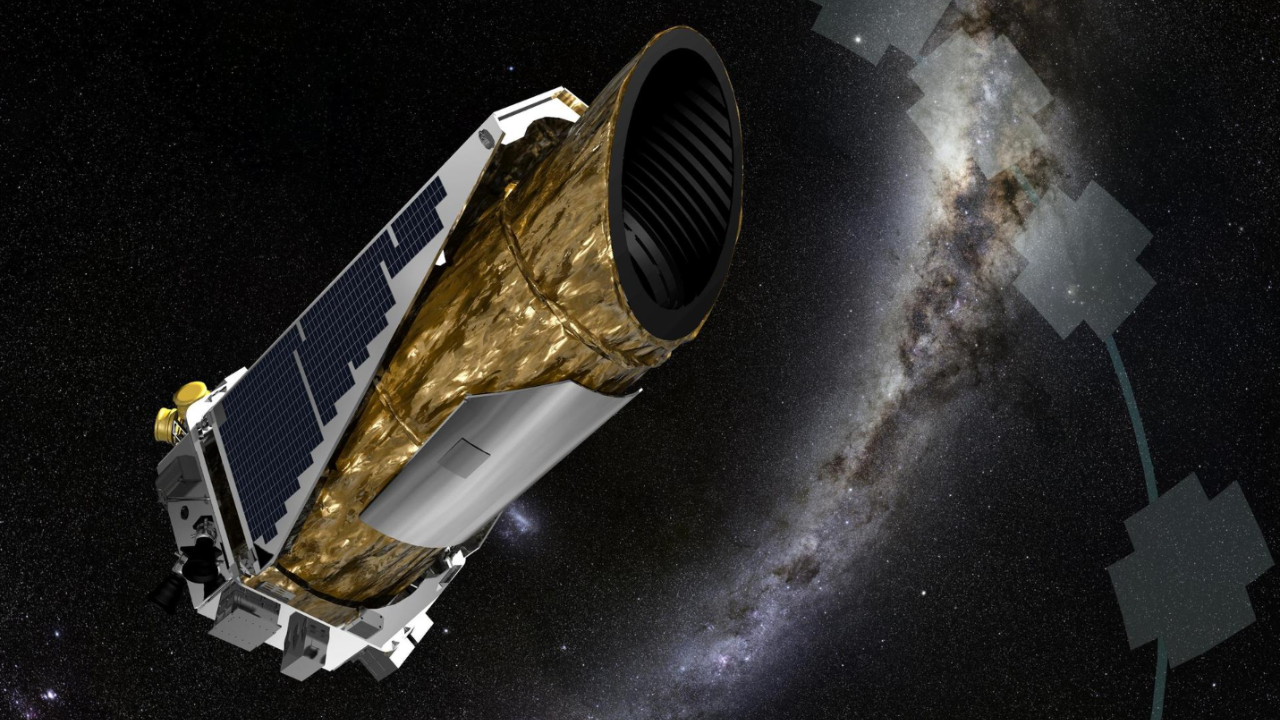

NEW DELHI: Astronomers have unveiled the discovery of a third planet within the Kepler-47 system, marking it as the most intriguing of binary-star systems. This new find, made using data from Nasa’s Kepler space telescope, was led by a team from San Diego State University. The newly identified planet, named Kepler-47d, is sized between Neptune and Saturn and orbits between two previously known planets in the system.

Kepler-47, notable for its three planets orbiting two suns, remains the only known multi-planet circumbinary system.Circumbinary planets are those that revolve around two stars. This unique arrangement was identified through the “transit method,” where the planets pass in front of their stars, causing a detectable dip in brightness from Earth.

The detection of Kepler-47d was challenging initially due to the weak transit signals. However, over time, the orbital plane of the middle planet shifted into a more favorable alignment, enhancing its transit signal significantly from undetectable at the start of the Kepler Mission to the most pronounced of the three over just four years.

Jerome Orosz, SDSU astronomer and lead author of the study, shared his early suspicions of a third planet back in 2012, but clarity only came with additional data. “We saw a hint of a third planet back in 2012, but with only one transit we needed more data to be sure,” Orosz explained. “With an additional transit, the planet’s orbital period could be determined, and we were then able to uncover more transits that were hidden in the noise in the earlier data.”

William Welsh, co-author and SDSU astronomer, expressed surprise at the findings: “We certainly didn’t expect it to be the largest planet in the system. This was almost shocking.”

The discovery enhances understanding of the Kepler-47 system, revealing that its planets are of very low density, even less than Saturn, which has the lowest density of any planet in our Solar System. The equilibrium temperature of Kepler-47d is approximately 50 degrees Fahrenheit, making it significantly milder compared to the innermost and much hotter planet of the system.

The study, recently published in the Astronomical Journal, was supported by Nasa and the National Science Foundation, highlighting the commonality of systems with closely-packed, low-density planets across our galaxy.

Kepler-47, notable for its three planets orbiting two suns, remains the only known multi-planet circumbinary system.Circumbinary planets are those that revolve around two stars. This unique arrangement was identified through the “transit method,” where the planets pass in front of their stars, causing a detectable dip in brightness from Earth.

The detection of Kepler-47d was challenging initially due to the weak transit signals. However, over time, the orbital plane of the middle planet shifted into a more favorable alignment, enhancing its transit signal significantly from undetectable at the start of the Kepler Mission to the most pronounced of the three over just four years.

Jerome Orosz, SDSU astronomer and lead author of the study, shared his early suspicions of a third planet back in 2012, but clarity only came with additional data. “We saw a hint of a third planet back in 2012, but with only one transit we needed more data to be sure,” Orosz explained. “With an additional transit, the planet’s orbital period could be determined, and we were then able to uncover more transits that were hidden in the noise in the earlier data.”

William Welsh, co-author and SDSU astronomer, expressed surprise at the findings: “We certainly didn’t expect it to be the largest planet in the system. This was almost shocking.”

The discovery enhances understanding of the Kepler-47 system, revealing that its planets are of very low density, even less than Saturn, which has the lowest density of any planet in our Solar System. The equilibrium temperature of Kepler-47d is approximately 50 degrees Fahrenheit, making it significantly milder compared to the innermost and much hotter planet of the system.

The study, recently published in the Astronomical Journal, was supported by Nasa and the National Science Foundation, highlighting the commonality of systems with closely-packed, low-density planets across our galaxy.

[ad_2]