[ad_1]

Subscribe

Apple | Google | Spotify | Amazon | Player.FM | TuneIn

Castbox | Podurama | Podcast Republic | RSS | Patreon

Podcast Transcript

You are probably familiar with, or have at least heard of, several of the great pre-Columbian cities in the Americas. Places like Tikal, Guatemala, Copan, Honduras, and Tenochtitlan, Mexico are some of the great legacies of the civilizations that came before.

However, all of these population centers were located Mesoamerica. Most of the people who lived in what is today the United States and Canada were nomadic and never built any large cities or structures.

….with was one major exception.

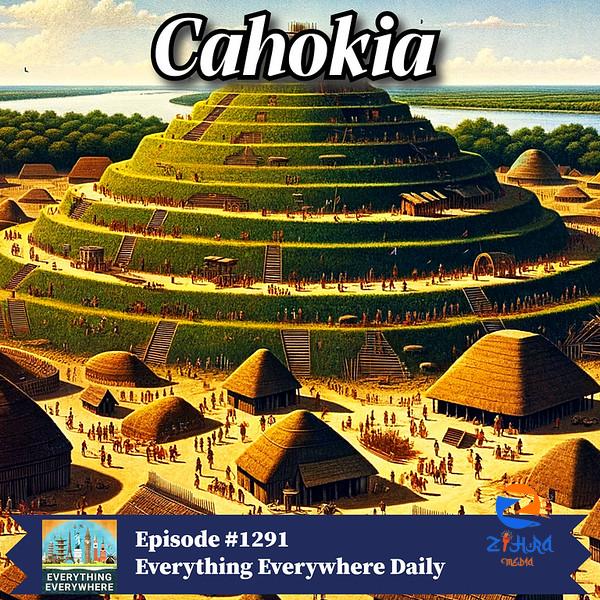

Learn more about Cahokia, the largest pre-Columbian settlement in North America, on this episode of Everything Everywhere Daily.

Before Europeans arrived in the new world, there were several major civilizations in the Americas, some of which all ready had fallen by the time Columbus arrived.

The Incas, the Olmecs, the Maya, and the Aztecs were just some of the people who left behind monumental stone structures that we can still see today.

All of these cultures had traits that would be defined as quote civilizations. They had highly complex social relations, a system of writing, and a highly organized system of intellectual, cultural, and material development.

But this gets into a weird distinction between a culture and a civilization.

When we use the term civilization, we tend to use it for cultures that built monumental structures.

But there were many advanced cultures in the Americas that didn’t necessarily leave behind the type of structures the Maya or the Aztecs did.

In many cases, they had very complex social structures, but their communities weren’t very big, and they didn’t necessarily build permanent structures out of stone.

When we look at cultures north of Mexico, most of the people were either nomadic or lived in small villages.

When Europeans showed up in the New World, they didn’t find any advanced civilizations in North America.

However, there was something that would be called an advanced civilization. Archeologists would call it the Mississippian culture. It is a name given to them retroactively, not one they used themselves.

If you haven’t heard of the Mississippian culture, it’s because they ceased to exist by the time Europeans arrived.

The Mississippians weren’t a single unified culture. They were groups of loosely associated people that existed in what is today the central and southeastern United States.

There were various Mississippian cultures extending from Georgia and northern Florida to Louisiana and East Texas in the south and up along the Mississippi River to Wisconsin and Minnesota, and then to Michigan in the North.

We have no idea what the Mississippians or their various subcultures called themselves, as we have no record of their language.

What we do know about Mississippians has come from archeology and artifacts that have been discovered.

There are some general traits that most of the Mississippian cultures in the region had in common.

They had an extensive trade network that was largely connected by the Mississippi River and its tributaries.

They had a very top-down social structure that was run by a small elite and a local community run by a chief.

They were largely agricultural, with their primary crop being maize or corn.

Moreover, they had very similar artifacts and mythology that are collectively referred to as the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex.

Perhaps the most significant cultural trait was that of large earthwork mounds.

The one site that had the largest earthworks and a central and strategic position for the entire Mississippian Culture was Cahokia.

Cahokia was located right across the river from the modern-day city of Saint Louis, Missouri.

The location of Cahokia and Saint Louis is not accidental. It is right at the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers, one of the most strategic locations in the United States.

Cahokia wasn’t discovered like most archeological sites are. Cahokia was never really lost, as those who lived near Cahokia always knew it was there. Moreover, the site has a very large and obvious mound that is pretty hard to miss.

When early French explorers and missionaries explored the Mississippi, they found the ruins of Cahokia, even if they didn’t really know what it was.

Archeologists didn’t begin studying Cahokia seriously until the end of the 19th and 20th centuries.

So what exactly was found at Cahokia, and what makes it special enough to do an episode on it?

Here is a very brief overview of the rise and fall of Cahokia.

There is evidence of human occupation of Cahokia going back at least 3,200 years. However, the earliest evidence of habitation of Cahokia as a Mississippian settlement goes back to the 8th century.

From about the year 700 until the year 1050, Cahokia was a small but growing settlement.

Then, around 1050, the site exploded in size and population. For about 150 years, Cahokia was at its peak and was the largest population center north of Mexico.

Estimates for the population at this time vary, but the most common estimates put the population between ten to twenty thousand people. I’ve also seen estimates that are as high as forty thousand.

Just to put that into comparison, that would have made Cahokia as large as London during that time and maybe even as large as Rome, which had shrunk considerably from its peak.

After the year 1200, Cahokia fell into decline, and by the year 1350, the site had been abandoned.

So, Cahokia has a history going back centuries, with its golden age lasting about 150 years.

So, what do we know about the site itself, the people who lived there, and how do we know it?

For starters, the word Cahokia was not the name for the site by the people who lived there. We have no clue what they called it because there is no written or oral history of the site that has been passed down.

The name Cahokia was taken from the local Cahokia tribe that lived in the area when French explorers first came through in the 17th century.

Because we have no written or oral history of Cahokia, everything we know comes from archeology. In some cases, the archeological evidence is very ambiguous and open to different interpretations. In other cases, especially with the help of advanced techniques, we can paint a much clearer picture of what happened.

Cahokia lies in a mud flat just east of the Mississippi River. There are several small lakes and ponds nearby. By analyzing the sediment and conducting an analysis of the pollen types at the bottom of the lake, it is possible to both date and get an idea of what sort of plants were growing nearby.

The story it tells is one of deforestation in the period when Cahokia was entering its peak, followed by a period of agriculture, in particular, the growing of corn or maize.

The organization of the city changed. Magnetic analysis of the soil shows that Cahokia changed from a small settlement that grew organically to a planned city that was based on a grid layout.

This occurred near the start of the Cahokia peak period as something happened that changed the importance of the site.

The signature feature of Cahokia, and the one thing that is still clearly visible today, is what is known as Monk’s Mound. The name Monk’s Mound comes from the fact that a small community of Trappist Monks lived at the site shortly after the arrival of Europeans to the region.

Monk’s mound is a large earthwork, in fact, the largest single one north of Mexico, that stands 100 feet or 30 meters high, or close to the height of a ten-story building. It consists of four different terraced layers and has an area of 13.8 acres or 5.6 hectares.

Core samples of the mound have been taken that give a glimpse as to how the mound was built.

The mound was built in phases over a period of decades, if not centuries. The final version of the mound contains over 814,000 cubic yards or 622,000 cubic meters of Earth.

All of the Earth used to make Monk’s Mound is believed to have been moved by hand as they had no draft animals.

At the top of the mound, there is evidence of a large structure. What the structure was or what it was used for isn’t known, but the best theories are that it was either a temple of some sort or the home of the leader of Cahokia.

There are multiple other smaller mounds around the site, many of which are burial mounds.

The burial sites show that there was a definite hierarchy in Cahokian society, with a wealthy upper class and a much poorer lower class.

One of the other fascinating things discovered has been called Woodhenge. It is a series of five concentric circles that were made out of timber. The circles are believed to have been constructed over a period of 200 years, with each successive circle being larger than the previous one.

Woodhenge is believed to have been used for astronomical purposes, similar to Stonehenge, hence the name.

The discovery I personally found the most interesting had to do with an analysis of strontium isotopes in tooth enamel.

There are several different isotopes of the element strontium. However, the ratios of them will differ in different locations. That means everyone who lives in the same area should have pretty much the same ratios of strontium isotopes in their tooth enamel.

You might not be able to tell exactly where someone was from, but you can tell if they grew up in the same place as someone else.

An analysis of teeth found in Cahokia shows that a geographically diverse group of people lived or at least visited the site. This is supported by the discovery of shells that are native to coastal regions hundreds of miles away from Cahokia.

Based on all the archeological evidence found at Cahocia so far, the big question is, why did this settlement get so big, and why did so many people travel such great distances to go there?

There are several theories which aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive.

The first of these is the obvious one, given its location at the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. Cahokia was a regional trading center.

If you remember back to my episode on the Mississippi River, you might remember that the Mississippi and all its tributaries form the largest navigable inland waterway system in the world.

In ancient times, this river would have served as a superhighway. Large canoes could easily travel up and down the river, trading goods. The logical point for everyone to meet would be in the center of the system, which is exactly why St. Louis is located there today.

Another theory holds that Cahokia was a site for important religious rituals. People may have flocked to Cahokia for religious purposes, which might have also coincided with trade missions.

Either way, one of the reasons why people traveled so far to visit Cahokia is because it was one of the few people where that would have even been possible.

The last big question, then, is why Cahokia was eventually abandoned. It was a great location, so no matter what happened, the geographic benefits of the site would have remained.

The answer is that no one is quite sure what happened. One theory is that the site became prone to flooding after the year 1200. This could have been caused by local deforestation in the area.

Another holds that a change in climate might have been the cause. A period known as the Medieval Warm Period ended right about the time Cahokia went into decline. The change in climate could have affected rainfall, which could have affected the course of the river.

Another theory holds that Cahokia might have been subject to raids, which would explain the defensive fortification found at the site.

Either way, there probably wasn’t any great disaster at Cahokia. The people simply migrated over time, splintered apart, and became the local native tribes in the Midwest.

Today, you can visit Cahokia Mounds State Park in Illinois. In 1982, it was made a UNESCO World Heritage Site. If you ever visit Saint Louis, I highly recommend visiting as it is close by and easy to visit.

Cahokia, as far as we know, was the largest populated settlement north of Mexico and held that distinction until the 18th century. As such, it is one of the most important archeological sites not only in North America, but in the world.

[ad_2]