[ad_1]

This is a second post from a set of comments I gave at the NBER Asset Pricing conference in early November at Stanford. Conference agenda here. My full slides here. First post here, on new-Keynesian models

I commented on “Downward Nominal Rigidities and Bond Premia” by François Gourio and Phuong Ngo. The paper was about bond premiums. Commenting made me realize that I thought I understood the issue, and now I realize I don’t at all. Understanding term premiums still seems a fruitful area of research after all these years.

I thought I understood risk premiums

The term premium question is, do you earn more money on average holding long term bonds or short-term bonds? Related, is the yield curve on average upward or downward sloping? Should an investor hold long or short term bonds?

1. In the beginning there was the mean variance frontier and the CAPM.

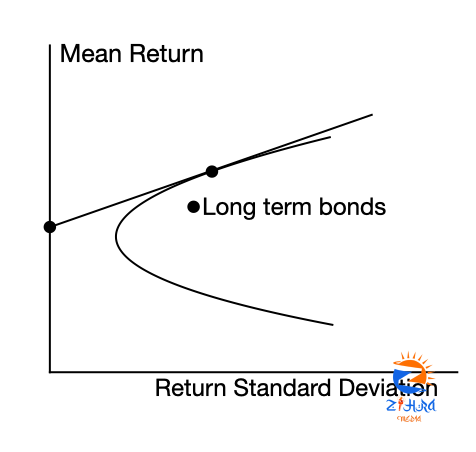

Long term bonds have an almost stock-like standard deviation (around 10%, 16% for stocks) with a mean return barely above that of cash or short term bonds. They look like yucky investments.

(They’re not, or not just based on this observation. Bonds are around 40% of the market. Good final exam question: Given the above picture, should a mean-variance investor get out of bonds? Is the market price and quantity irrational? Hint: Individual stocks are also inside the frontier.)

More precisely, short-term bonds or the “risk free rate” are the best investment for risk-averse investors. Long term bonds are at best part of the risky portfolio. Less risk averse investors hold some of them for slightly better return and diversification.

That leads to the standard presupposition that long-term bonds have higher returns, and the yield curve slopes up, to compensate for their extra risk. That isn’t quite right — average return depends on betas. Long term bonds have higher returns, if their extra risk covaries with stock risk. They could be “negative beta” securities, but that is unlikely. Higher interest rates lower stock prices too.

Now, your presupposition is that long term bonds should have the lowest yields, being safest, and short-term bonds should have a higher mean return to compensate for extra risk.

But we’re talking about nominal bonds, not indexed bonds. The risk-free proposition holds if real interest rates vary, but inflation does not.In that case, short bonds have roll-over risk for long term investors, and long bonds have steady payouts. If inflation varies but real rates are constant, then short-term bonds have less risk for long term investors.

That suggests an interesting view: Until 1980, inflation was pretty variable, and we should see upward sloping term structure and risk premium. After 1980, or at least after 1990, inflation was stable and real interest rates varied. The risk premium should turn around.

3. That too is simplistic, because of course I’m looking again at variance not beta. Now, inflation reliably falls in recessions (see graph). Interest rates also fall in recessions, so bond prices rise. That means bonds are great negative-beta investments. Bonds overall should have very low returns. And this pattern has become much stronger since the 1980s, so bond returns should have gone down.

They did. In all the arguments about “savings glut,” “low r*” and so on, I never see this basic mechanism mentioned. Bonds are great negative-beta securities to hold in a recession or financial crisis.

And, that holds especially for government bonds. Look at 2008, and remember that prices move inversely to yields. Holding 10 year government bonds would have been much better than holding BAA bonds! That saving grace in a severe financial crisis, when the marginal utility of cash was high, might well account for some of the otherwise much higher yield of BAA bonds.

But today we’re looking at the term premium, long bonds vs short bonds, not the overall value of bonds. Now, short bond yields go down a lot more than long term yields. But price is 1/(1+y)^10, and the short bonds mature and roll over. It’s not obvious from the graph which of long or short bonds has a better return after inflation going through the financial crisis. But that is easy enough to settle.

But I didn’t

Reading Gourio and Ngo made me realize this cozy view was a bit lazy. I was looking at covariance of return with one-period marginal utility, forgetting the whole long-horizon investor business that brought me here in the first place. The main lesson of Campbell and Vieira’s work is that it is nuts to do one-period mean and alpha vs beta analysis of bond returns. More precisely, if you do that you must include “state variables for investment opportunities.” When bond prices go down bond yields go up. You will make it all back. That matters.

Yet here I was thinking about one-period bond returns and how they covary with instantaneous marginal utility. What matters for the long-horizon investor is how a bad outcome covaries with remaining lifetime consumption, remaining lifetime utility. Returns that fall in a recession shouldn’t matter much at all if we know the recession will end.

There is, of course, one special case in which consumption today is a sufficient statistic for lifetime utility — the time-separable power utility case. To use that, though, you really have to look at nondurable consumption, not other measures of stress. And, of course, I’m assuming that long-term investors drive the market.

Normally we do not impose the consumption-based model. So it remains true, if you are thinking about expected returns in terms of betas on various factors, it is absolutely nuts not to think about long term bonds with factors such as yields that are state variables for future investment opportunities.

Gouio and Ngo use a consumption-based model, but with Epstein Zin utility. (Grumble grumble, habits are better for capturing time-varying risk premeia.) The power utility proposition that today’s consumption is a sufficient statistic for information about the future also falls apart with Epstein Zin utility. A lot of the point of Epstein Zin based asset pricing is that expected returns line up with consumption betas, but also and often predominantly with betas on information variables that indicate future consumption.

Here, my comment is not critical, but just interpretive. If we want to understand how their or any model of the bond risk premium works, we cannot think as I did above simply in terms of returns and current consumption. We have to think in terms of returns and information variables about future consumption, a set of state-variable betas. Or, following back to Campbell and Viceira’s beautiful insight, we should think about returns as increases in the whole stream of consumption. We should think about portfolio theory in terms of streams of payoffs and streams of consumption, not one-period correlations and state variables.

What’s the answer? Why do Gourio and Ngo find a shifting term premium? Well, I finally know the question, but not really the intuition of the answer.

You can see how my attempt to find intuition for bond premiums follows advances in theory, from mean-variance portfolios and CAPM, to ICAPM with time-varying investment opportunities, which bonds have in spades, to a long-term payoff view of asset pricing, to time-varying multi factor models, to the consequences of Epstein Zin utility.

But contemporary finance is now exploring a wild new west: “institutional finance” in which leveraged intermediaries are the crucial agents and the rest of us pretty passive; segmented markets, safe asset “shortages” “noise traders” and pure supply and demand curves for individual securities, neither connected across assets by familiar portfolio maximization nor connected over time by standard market efficiency arguments. With this model of markets in mind, obviously, who should (or can!) buy long term bonds, and how we understand term premiums, will be vastly different.

So, I go from a very settled view with just a little clarification needed — long vs short term bond recession betas — to seeing that the basic story of term premiums really is still out there waiting to be found.

[ad_2]

.tiff)

.tiff)

.tiff)