[ad_1]

This is another post from an Economic Policy Working Group meeting at Hoover, in which simple undergraduate supply and demand analysis, creatively applied, leads to a surprising result.

Casey Mulligan presented “Prices and Policies in Opioid Markets.” Paper, slides and video of the presentation.

Once prescription opioids became an evident crisis, the government took steps to restrict the supply, raising the price. Yet opioid consumption and overdoses went up. Explain that Mr. Chicago economist!

Here’s the clever answer:

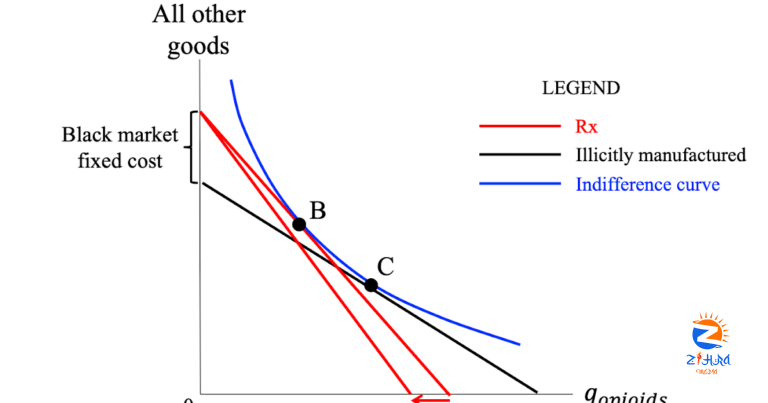

There are two ways to buy opioids, 1) legally or semi-legally; i.e. get opioids that come from pharmaceutical companies and are prescribed to someone by a doctor or 2) illegally.

There is a fixed cost of entering the illegal market. .”.Avoiding theft, acquiring self-dosing skills, or overcoming fear of needles. …establishing a trusting relationship with a drug dealer….” But the cost per dose of illegal drugs is typically less than for legal drugs.

So, imagine a drug user starting at B. At that price for legal (red) and illegal (black) drugs, the user chooses legal drugs at point B. Now raise the price of legal drugs, as shown by the arrow. If the user stayed with legal drugs, he or she would use less. But now there is an option, incur the fixed cost and buy illegal drugs on the black line. At the higher price for legal drugs that makes sense. But since the marginal cost of illegal drugs is lower, once the user has overcome the fixed cost, he or she uses more.

The paper checks several predictions of the model, including timing that the surge in illegal use coincided with greater regulation of legal drugs. Another test (sad):

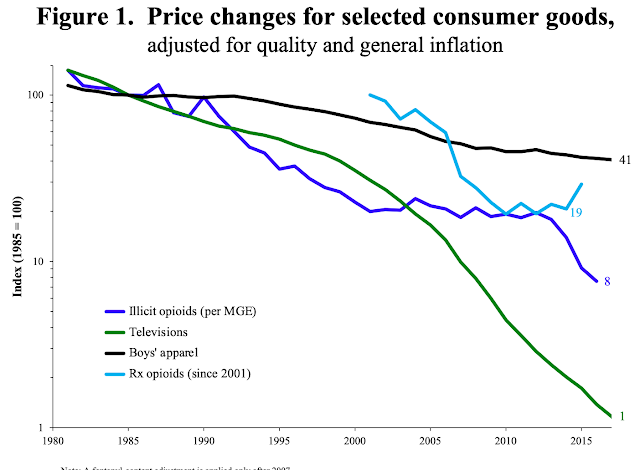

Here’s what happened to prices

“In the earlier years, opioid subsidies are created and expanded for patients and prescribers while regulations are relaxed. In about 2010 policies begin to swing in the other direction as the with reformulation (see below) and programs discouraging prescription supply to secondary markets. … enforcement of illicit-drug prohibitions was less of a priority between 2013 and 2016.

(i) heroin was significantly more expensive per MGE than Rx opioids in the 1990s, (ii) illicit opioids became cheaper over time, especially since 2013, and ultimately cheaper than Rx opioids, and (iii) beginning in about 2011, Rx opioids became more expensive or difficult to access for nonmedical use due to regulatory and fiscal changes.

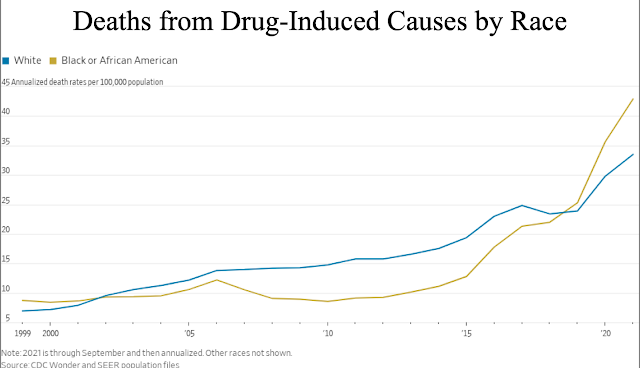

Second fact,

The model makes sense of this pattern. Under the reasonable assumption that Blacks have a harder time getting prescription opioids, they would naturally be less open to the prescription opioid boom. But once illegal opioids become a lot cheaper, Black users who are largely confined to the illegal market anyway, expand greatly.

The discussion was interesting. Most of the commenters wanted to add sensible complications to the model. The fact that opioids are addictive seems like an obvious one. But admire the art in what Casey has done: stripped the model down to the absolute minimum that explains the phenomenon. Stripping models down is hard.

[ad_2]