[ad_1]

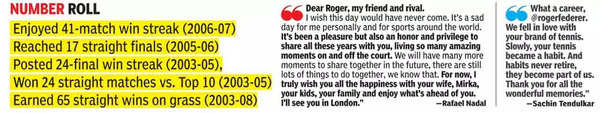

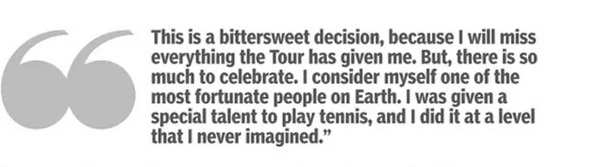

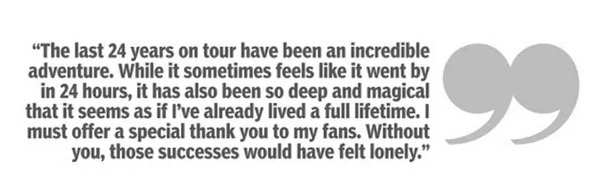

And just like that, it was over. You always knew it was round the corner, but there was a “maybe one last time” rider flickering all the time. Now we know it’s not happening. There will be no farewell tour, no grind of midnight despair. Roger Federer will not be performing for us beyond the Laver Cup next week.

The final memory of Federer playing a match at Wimbledon will be the bagel that he suffered at the hands of Hubert Hurkacz. But that’s fine. Life was never meant to be a fairytale, so why an exemption for Federer?

When you go back, you can always see moments when he could have chosen the fairytale ending. A retirement at the end of 2017, with two Slams on a phenomenal return, and there would have always been that afterglow of a Pete Sampras-esque exit.

To my tennis family and beyond,With Love,Roger https://t.co/1UISwK1NIN

— Roger Federer (@rogerfederer) 1663247919000

But for one of the greatest artists of sport, a mundane exit was a conscious choice. The man who has the highest number of Wimbledon titles goes out with a bagel in his last outing on grass. Or the image of a player whose body was “god-gifted” – according to his fiercest rivals – fighting to become fit for one last try, Federer the master chose to be the common man. Which he truly believed he was!

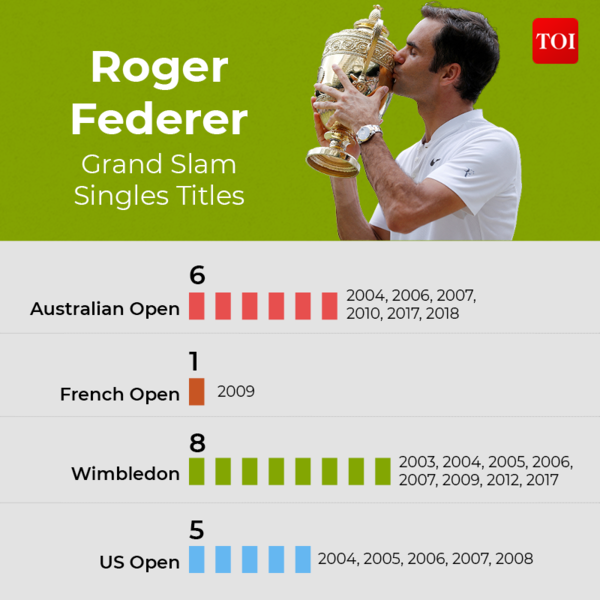

Roger Federer holding his 20 Grand Slam tournaments winner’s trophies. (AFP Photo)

The little boy in his early teens used to cry because he had to spend the week in the Swiss tennis academy in Lausanne, where French is spoken. For little Roger, the comfort of his hometown Basel, where he could speak German, was more important. But not for all those who were around him. They saw probable greatness, and Federer was okay to accept it and fight on.

❤️ https://t.co/YxtVWrlXIF

— Roger Federer (@rogerfederer) 1663247998000

He skipped his first Wimbledon champion’s ball as a junior champ because he had got a wild card in an ATP event in Switzerland. It was a battle in itself, but he accepted it. Losing to Tim Henman right after beating Pete Sampras at Wimbledon in 2001 would have been crushing, but he didn’t give up. Two years of dealing with the so-close-yet-so-far idea wasn’t easy, but he dealt with it. When he talks about his first Championship point at Wimbledon, he proves he has always been one of us: “I was just hoping Philippoussis hits that ball wide so I don’t have to win the match point on my own.”

Art just happened. Federer was never the conscious artist that we believed he is. But as it happened, he did make sports writers run out of adjectives. How Federer became the reference point of genius is probably unknown, but by 2005, he had learnt to acknowledge that as well. “It’s not a shame losing to the Greatest of All Time,” Andre Agassi said after the 2005 US Open final. Federer had merely won his sixth. But he smiled and nodded. He knew he had to bear the cross of genius.

The flick of the wrist, the forehand, the easy service action, the single handed backhand that often didn’t land but just looked beautiful, all made us believe that the sport begins and ends with one man. Till Rafael Nadal happened.

Nadal, with everything that Federer wasn’t on court, became the greatest counterpoint that 21st century sport could offer. From a world of ethereal beauty, Federer was down in the dangal, battling bloody-nosed.

“I would never have been the player that I was but for Nadal,” Federer says. Three back-to-back final losses at the French Open and the 2008 Wimbledon defeat to Nadal made Federer soul-search for the first time since his teens, when he had given up his outward tempestuousness to cultivate a strength that made him boss the Roddicks and Hewitts for long.

It was probably this soul-searching that resulted in the most defining moment of his career, winning the 2009 French Open. Rafa had lost the day before to Robin Soderling and Federer was two sets down to Tommy Haas in the fourth round. If it was a year earlier, Federer would probably have not buckled down the way he did after that. An unbelievably courageous forehand to save the break-point in the eighth game of the third set against Haas sparked off one of the greatest title rides. Monfils in quarters, Del Potro in semis and Rafa-slayer Soderling in final – it was difficult every step of the way, but Roger was ready to grind. The Swiss genius was fighting to prove his credential, to show the world he belongs on clay too.

If Federer had decided to go at the turn of the decade, no one would have raised an eyebrow. He was 30, had crossed Pete Sampras’ record by then and had won on all surfaces. There was nothing more to prove. But Federer kept reminding us time and again he would leave the day he feels he doesn’t feel like training any more.

Roger Federer holding up the Wimbledon Championships trophy after winning each of his eight titles in 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2012 and 2017. (AFP Photo)

The aura of the unbeatable Federer had been broken, but the fight never left him. Compared to his two great rivals, the fighting spirit of Federer is probably an under-rated area, but the very fact that he was changing the definition of tennis proved his steel. It was those defeats that spurred his desire to come back. He wasn’t supposed to come back from a serious injury in 2017 and win those three Slams by January 2018. And probably he wasn’t supposed to lose the 2019 Wimbledon final when he had two championship points on his own serve.

Doesn’t matter, Roger…thank you for the entertainment!

[ad_2]