[ad_1]

With food and medicine supplies threatened across Ukraine, domestic and international food manufacturers, distributors and aid workers are mobilizing to keep grocery stores and pharmacies open and shelves stocked.

In recent days, much of Ukraine’s domestic food production and distribution ground to a halt, triggering shortages in parts of the country, especially in areas hardest hit by the Russian invasion. So far, that hasn’t escalated into widespread hunger, thanks in part to a domestic and international effort to get food around the country.

Russia and Ukraine had agreed Saturday to open humanitarian corridors for evacuating civilians from the besieged eastern cities of Mariupol and Volnovakha, and for resupplying them with food and medicines, but the agreement collapsed as Kyiv accused Moscow of violating the cease-fire.

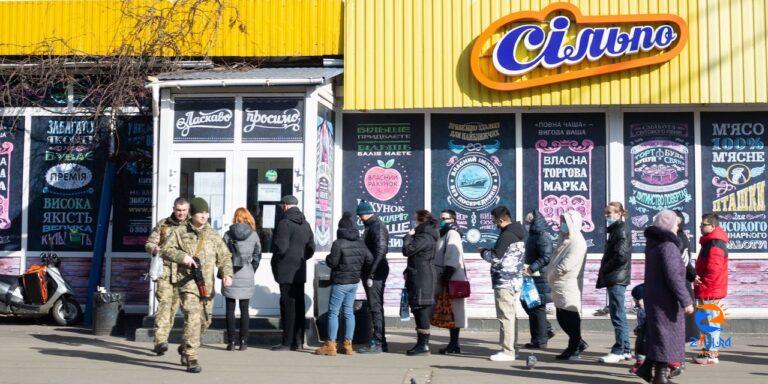

Earlier this week, Fozzy Group, Ukraine’s largest supermarket chain, had plenty of food—including fresh produce like cucumbers and tomatoes—sitting in warehouses dotted around the country, according to a spokesman. But a shortage of drivers and loaders, active fighting on roads, and a lack of gasoline is hampering the movement of supplies from its warehouses to stores.

Over 90% of the company’s roughly 1,000 stores—operating under banners like Silpo, Fora and Fozzy—are open, including most stores in Kyiv, said the spokesman.

Even in Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second-largest city and site of some of the heaviest shelling by Russian forces in the invasion, Fozzy has been trying to keep stores mostly open, sometimes closing them for an hour or two when it determines the situation is getting dangerous, but then reopening as quickly as possible. The company is regularly alerting shoppers about store hours and product availability on its websites and through social media, said the spokesman.

Fozzy’s chain of restaurants are closed. Its chain of pharmacies, Bila Romashka, is open. The company has taken to

Instagram and other social media to call for volunteers to help drive trucks and load goods from its six logistics centers.

Dutch food retailer

International said as of Monday 95% of its stores in western Ukraine, further away from the most intense fighting, remained open, although many were operating only for a few hours. The company, which has 65 supermarkets across Ukraine, has set up an internal fund to assist its Ukrainian operations in procuring products locally from existing suppliers. It is simultaneously working to establish new suppliers for essential goods to send to its distribution center in Ukraine, located about 60 miles from the Polish border.

“With the ongoing escalation of the war, and the prospect of the local supply chains being further impacted, it is essential to ready the ability to maintain supply from our operations in neighboring countries,” said Spar.

Imports from foreign suppliers have been disrupted. Dr. August Oetker KG, a German company that usually exports yeast, baking powder and other baking ingredients from Germany, Poland and Romania to Ukraine, halted this last week and closed its warehouse in Kyiv, said a spokesman. “There are no trucks who can deliver our goods at the moment,” he said.

To help fill the void, global nonprofits are ramping up efforts to get food to Ukrainians. The World Food Programme said its first trucks of food rations to the country arrived earlier this week at Ukraine’s border with Poland. The food is coming from Turkey, according to a spokeswoman, who says WFP’s focus will initially be on providing food for people clustered at the border, mostly women and children.

In areas where people are on the go and can’t cook, the WFP is offering emergency rations of tinned and packaged food—its first shipment contains 200 tons of these. In places where people still have access to stores and cooking facilities, it is offering cash and food vouchers.

WHO medical aid for Ukraine is stored in a warehouse after arriving at Warsaw Chopin Airport in Poland this week.

Photo:

WHO/REUTERS

The International Committee of the Red Cross, meanwhile, is trying to bring in medical supplies. But trucks “simply can’t move because of the hostilities,” said a spokesman. The Red Cross has 600 people on the ground in Ukraine but in areas of active fighting, staff are having trouble moving around. The organization will initially focus on bringing in medicines, tarpaulin and blankets, he added.

Some medical supplies are already running low. The World Health Organization on Sunday warned that hospitals are running out of medical oxygen because trucks can’t transport it from plants, due to road disruptions and a lack of drivers willing to make the journeys.

Ukraine was in the midst of a polio vaccination campaign for young children after a toddler suffered paralysis from the virus in October, the first case in more than five years. The campaign began on Feb. 1 but was halted when fighting broke out.

The WHO is air freighting supplies for trauma care to neighboring Poland and has a warehouse of supplies in Ukraine. Doctors Without Borders is also working on securing safe routes for medical supplies to move around the country, said Kate White, an emergency manager for the international aid organization.

“We can get kits to the country,” said Jarno Habicht, WHO’s representative in Ukraine. “But are they getting where they are most needed in the health system, that’s the question.”

Those difficulties are creating dangerous shortages of drugs like insulin, according to several groups working in the country. “What we’re hearing from our contacts within hospitals and health facilities inside Ukraine is there is a significant shortage of insulin right now,” said Doctors Without Borders’ Ms. White. “For insulin-dependent diabetes patients that is a significant concern.”

a major insulin supplier, said deliveries from its warehouse have been disrupted due to shortages in driving staff. “We are doing everything we can to get medicines to the patients that need them either through pharmacies or humanitarian organizations,” a company spokeswoman said.

Healthcare officials and aid workers have also warned that the crowded conditions faced by refugees will likely lead to a surge in Covid-19 infections. “Infectious diseases ruthlessly exploit the conditions created by war,” said Bruce Aylward, senior adviser to the WHO director-general. That is because of increased transmission, but also because lack of healthcare means higher numbers of avoidable deaths.

Write to Saabira Chaudhuri at saabira.chaudhuri@wsj.com and Denise Roland at Denise.Roland@wsj.com

Copyright ©2022 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8

[ad_2]