[ad_1]

I’m working madly to finish The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level. This is a draft of Chapter 21, on how to think about today’s emerging inflation and what lies ahead, through the lens of fiscal theory. (Also available as pdf). I post it here as it may be interesting, but also to solicit input on a very speculative chapter. Help me not to say silly things, in a book that hopefully will last longer than a blog post! Feel free to send comments by email too.

Chapter 21. The Covid inflation

As I finish this book’s manuscript in Fall 2021, inflation has suddenly revived. You will know more about this event by the time you read this book, in particular whether inflation turned out to be “transitory,” as the Fed and Administration currently insist, or longer lasting. This section must be speculative, and I hope rigorous analysis will follow once the facts are known. Still, fiscal theory is supposed to be a framework for thinking about monetary policy, so I would be remiss not to try.

|

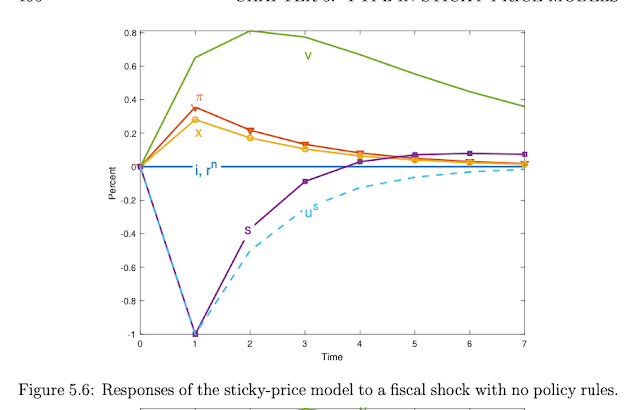

| Figure 1. CPI through the Covid-19 recession. |

Figure 1 presents the CPI through the covid recession. Everything looks normal until February 2021. From that point to October 2021 the CPI rose 5.15% (263.161 to 276.724), a 7.8% annual rate.

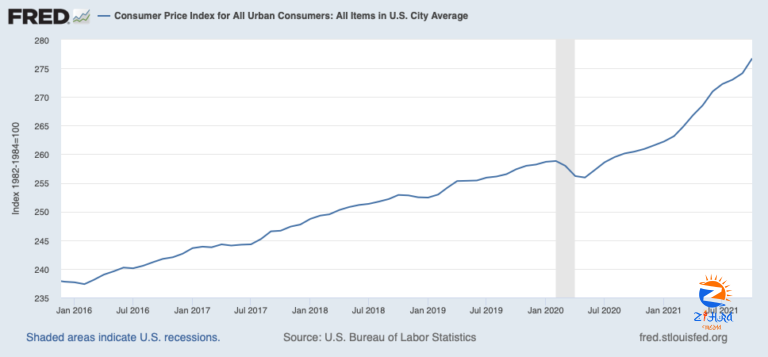

What happened, at least through the lens of the simple fiscal theory models in this book? Well, from March 2020 through early 2021, the U.S. government — Treasury and Fed acting together — created about $3 trillion new money and sent people checks. The Treasury borrowed an additional $2 trillion, and sent people more checks. M2, including checking and savings accounts, went up $5.5 trillion dollars. $5 trillion is a nearly 30% increase in the $17 trillion of debt outstanding at the beginning of the Covid recession. Table 21.1 and Figure 2 summarize. ($3 trillion is the amount of Treasury debt purchased by the Fed, and also the sum of larger reserves and currency. Federal debt held by the public includes debt held by the Federal Reserve.)

|

| M2, debt, and monetary base (currency + reserves) through the Covid-19 recession. |

|

Some examples: In March 2020, December 2020, and again in March 2021, in response to the deep recession induced by the Covid-19 pandemic, the government sent “stimulus” checks, totaling $3,200 to each adult and $2,500 per child. The government added a refundable child tax credit, now up to $3,600per child, and started sending checks immediately. Unemployment compensation, rental assistance, food stamps and so forth sent checks to people. The “paycheck protection program” authorized $659 billion to small businesses. And more. The payments were partly designed as economic insurance, transfers from people doing well during covid to those who had lost jobs or businesses, and efforts to keep businesses from failing. But they were also in large part, intentionally, designed as fiscal-monetary stimulus to boost aggregate demand and keep the economy going. The massive “infrastructure” and “reconciliation” spending plans occupied the Congress through 2021, adding expectations of more deficits to come.

From a fiscal-theory perspective, the episode looks like a classic fiscal helicopter drop. There is a large increase in government debt, transferred to people, who do not expect that debt to be repaid. It is a“fiscal shock,” a decline in surpluses s_t, with no expectation of larger subsequent surpluses. Of course it led to inflation!

We might try to think of the episode as a rise in debt B_t without future surpluses that raises expected inflation. But this does not look like expected inflation. The Fed, Administration, survey expectations, low interest rates, and private forecasts were completely surprised by inflation. As of the end of 2021 the Fed and Administration continue to proclaim it “transitory,” i.e. not expected to continue, and interest rates remain low. Survey expectations have risen. The divergence between survey expectations and bond markets is intriguing, and the expectations hypothesis is known for its failures at short-run forecasting. But even this rise only came in the middle of the event, not with the bond sales as a rise in expected inflation would do.

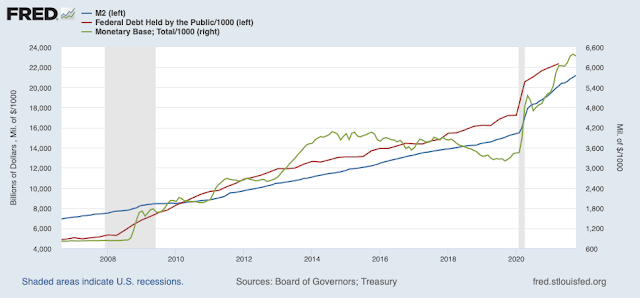

But the frictionless model is too simplistic to track an episode. We must think of the event with at least some sticky prices and long-term debt in mind. As a start, one might think of the fiscal shock with no interest-rate response and sticky prices of Figure 5.6. That model quickly resolves a first discrepancy: In the frictionless model, a fiscal shock does not raise the value of debt, and an AR(1) fiscal shock results in a lower value of debt. In the event, the value of debt rose. But the value of debt also rises in the sticky-price model of Figure 5.6. Higher inflation with constant nominal interest rates lowers the real rate, so the discount-rate effect accounts for the higher value of debt despite lower surpluses. In this view, the higher debt-to-GDP ratio is transitory and will be slowly inflated away. (The figure posits that 40% of a fiscal shock is inflated away, and 60% is eventually repaid. This event looks like a larger fraction will not be repaid. But the Figure still gives a first sense of dynamics.)

In the model, Figure 5.6, inflation starts immediately, while there was a year delay in the data. One might want a different model of price stickiness, or model the anecdotal evidence that people waited a year to start spending their newfound money. Most likely, the first stimulus checks did not fully reveal to people how large the final fiscal expansion would be. My expectations suffered several shocks in the same direction; I did not expect $5 trillion when it started. Or, perhaps the expectation that the debt would not be repaid took some time to settle in. Perhaps the debate over the large “build back better” bill cemented expectations on that score.

A monetarist might object that this event was (finally) proof of MV=PY. Helicopter yes, but helicopter money, not helicopter bonds. M2 rose $5.5 trillion, the rest is irrelevant. But we can ask all the questions of Section 14.1 about helicopter drops: Suppose the M2 expansion had been entirely produced by purchasing existing Treasury securities, with no deficits. Would this really have had the same effect? Are people starting to spend their M2 because they don’t like the composition of their portfolios, which have too much M2, paying 0.01% (Chase), and not enough one-year treasurys paying 0.1%? Or are they simply spending extra “wealth?” Suppose the Federal Reserve had refused to go along, and the Treasury had sent people Treasury bills directly. Would that not have stoked the same inflation? The fiscal expansion, the wealth effect, is the natural interpretation of this episode.

Why did this stimulus cause inflation, and that of 2008, or the deficits from 2008 to 2020, did not do so? Federal debt held by the public doubled from 2008 to 2012, as inflation went nowhere. (Figure 5.6.) From the fiscal theory point of view, the key feature is that people do not believe this debt will be paid back. (In principle discount rates or real interest rates could be different, but in this case they are nearly the same.) So why, this time, did people see the increase in debt and not infer higher future surpluses, while previously they did? Several speculations suggest themselves.

First, we can just look at what politicians said. In 2008 and following years, the Administration continually offered stimulus today, but promised deficit reduction to follow. One may take those promises with a grain of salt. But at least they bothered to try. This time there was no talk at all about deficit reduction to follow, no policies, no plans, no promises about how to repay this additional debt. Indeed, long-run fiscal policy discussion became focused on how low interest costs, r<g, and modern monetary theory allow painless fiscal expansion. The discussion of tax hikes in the spring and summer of 2021 focused entirely on paying for some of the ambitious additional spending plans, not repaying the Covid helicopters.

Second, much of the expansion was immediately and directly monetized and sent to people as checks. The previous stimulus was borrowed, and funded government spending programs that have to gently work their way into people’s incomes. Following 2008, M2 did not rise as much as debt. The QE operations were mostly confined to a switch of bank assets from Treasury debt to reserves, as we see from the contrast between the monetary base (currency + reserves) and M2 in Figure 2. (Note the base is on a different scale.)

Money and bonds may be perfect substitutes, but who gets the money or debt and how can still matter. Traditional buyers of Treasury debt have savings and investment motives. (Think of an insurance company.) If the Fed instantly buys the debt, and Treasury sends reserves (checks) to people, the larger debt goes quickly to people who are likely to spend gifts quickly. Debt sold to traditional bond purchasers, who show up at Treasury auctions or buy from broker-dealers, sends a different signal than money simply created and sent to people. This statement implies some slow-moving capital frictions and heterogeneity, but most of all it echoes the idea that the institutional context of debt expansion matters to expectations of its repayment. We distinguished Treasury actions as a share issue and reserve creation as a split, differing only in the expectations of repayment that each engenders. We distinguished “regular budget” and “emergency budget” deficits, likewise signaling backed vs. unbacked expansions. Since the desire was stimulus, and stimulus requires the government to find a way to communicate that the debt will not be repaid, one can regard the effort as a success at its goal, finally overcoming the expectations of repayment that made previous stimulus efforts fail, guilty only of having overdone it.

Third, the Covid-19 economic environment was clearly different. The pandemic and lockdown shock is fundamentally different from a banking crisis and recession shock of 2008. GDP and employment fell faster and further than ever before, and then rebounded most of the way, also faster than ever before. From a macroeconomic point of view, the Covid-19 recession resembles an extended snow day rather than a traditional recession. One might call that a “supply shock,” as the productive capacity of the economy is temporarily reduced, but demand falls as well, for the same reasons that people don’t rush out to buy in a snow day either. (I write “from a macroeconomic point of view.” A million people died in the U.S., an ongoing public-health disaster. Many people suffered lost jobs and businesses.) Roughly speaking the economy was operating at its reduced “supply” capacity all along, not needing extra “demand.” Providing that “demand” could reasonably spill more quickly to inflation.

Will inflation continue? You’ll know the answer, and I don’t. But it’s worth writing how one might think about the question. The $5 trillion total fiscal expansion is an approximately 20% expansion in debt. If the expansion came with no change at all in expected future surpluses, that will result in a cumulative 20% price-level rise, once we work through all the dynamics. Several commentators view this outcome positively: An unexpected crisis is met with a Lucas-Stokey state-contingent default, a wealth tax, via inflation. Whether that optimal tax argument extends to stimulus payments rather than insurance or war-fighting is a bit more tenuous. But the effect will be to have financed the stimulus payments by a wealth tax on government bonds.

But that’s it. Whether inflation continues depends on future fiscal and monetary policy, and whether people have changed their expectations of future repayment and the underlying monetary-fiscal regime. If people regard the stimulus payments as “emergency budget” expenditures that will not be repaid, but the existing 100% of GDP debt still to be repaid, and the additional borrowing of the years ahead back to the “regular budget,” that will be repaid, fiscal inflation need not continue. If, however, having changed their expectation that greater debts, especially those that finance cash transfers, are now not to be repaid, additional deficits will lead to additional inflation, and additional debt issues will just raise nominal interest rates.

The models remind us though that bad fiscal news can only affect unexpected inflation, though sticky prices, long-term debt, and endogenous policy responses can smear out that basic logic over many years. Once Covid passes, the U.S. will likely be back on the previous track of trillion dollar deficits in good times and $5 trillion in each crisis. Not sustainable, but not news. Thus, if the 2020s are the decade of fiscal inflation, that will likely come from changing expectations of repayment, or a changing (higher) discount rate, not particularly important news about short-term deficits. Such expectations can shift slowly, hope triumphing over experience several times in a row, which along with the smoothed dynamics can lead to a decade of inflation, not a one-time price-level jump.

What of monetary policy? The episode and the decade will likely offer different interpretations, which may help to sort out the fiscal theory plus rational expectations view, and the traditional adaptive expectations view, in which higher interest rates reliably lower inflation, interest rates rather than fiscal affairs are the main cause of inflation, and swift more than one-for-one response is necessary to keep inflation from spiraling out of control.

From the traditional perspective, the Fed’s monetary policy in 2020 and 2021 is a significant institutional failure. The Fed was caught completely by surprise. The Fed claims that supply disruptions caused inflation. But the Fed’s main job in the conventional reading is to calibrate how much “supply” the economy can offer, and then adjust demand to that level and no more. A central bank offering supply as an excuse for inflation is like the Army offering that the enemy chose to invade as excuse for losing a war. If the Fed is surprised that containers can’t get through ports, why does it not have any of its thousands of economists calculating how many containers can get through ports? The answer is that the Fed’s “supply” modeling is pretty simplistic, relying mainly on the non-inflationary unemployment rate (NAIRU) concept. More deeply, the Fed worked with Treasury on the stimulus in the first place, misdiagnosing the economy’s fall as simple lack of “demand,” not disruption due to a virus and lockdowns.

More broadly, the general policy discussion involving Fed, Administration, politicians and pundits relating inflation to specific markets and supply shocks, like containers stuck in ports, confuses relative prices for inflation. Supply shocks cause relative price changes. Strawberries are more expensive in winter. That’s not inflation. Aggregate supply is the relationship between the rise of all prices and wages together, and the total amount produced in the economy. That is a question about the nature of shocks to the Phillips curve, which may or may not have anything to do with supply restrictions of individual markets. Inflation is a decline in the value of the dollar. In that sense all inflation comes from “demand.” Blaming inflation on microeconomic shocks, corporate greed, producer collusion, speculators, hoarders, middlemen, price-gougers, and other hunted witches goes back centuries. Trying in vain to talk or threaten down prices goes back centuries. The Roosevelt Administration tried to cure deflation by creating monopolies to raise prices. Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon and Ford all pressured companies to lower prices and unions to lower wages. None of it worked. The Biden Administration’s effort to attack oil companies for collusion will fail just as predictably.

Going forward, in this conventional reading of monetary policy, the Fed seems primed to repeat the mistakes of the 1970s. The Fed of the early 1970s also blamed inflation on price shocks, and declared inflation to be transitory. The Fed’s 2020 strategy review practically announces a return to 1970s policy. The Fed will deliberately let inflation run hot for a while, running down a static Phillips curve, in an effort to boost employment. The Fed will wait until inflation persistently exceeds its target before doing anything about it. The Fed will return to filling “shortfalls” rather than stabilization, a return to the belief that even at the peaks the economy can never run too hot. The Fed understand “expectations” now, unlike in 1971, but views them as a third force, amenable to management by speeches, rather than formed by a hardy and skeptical experience with the Fed’s actions, a durable “rule” or “regime.” And the “strategy” is so flexible that pretty much any discretionary action can be justified. To be a bit charitable, this strategy was developed before 2020 and is designed to ward against zero-bound deflationary spirals with ample inflationary forward guidance. But if inflation continues, that will now be an exquisite Maginot lineThe absence of contingency planning for inflation will be laid bare. In the conventional reading,“anchored” expectations come from one place only: belief that the Fed will, if needed, replay 1980: Sharp persistent interest rate increases that may cause a painful recession, but the Fed will stick with them as long as it takes. But though our current Fed says it has “the tools” to contain inflation, it’s remarkably reticent to state just what those tools are. Do people believe our Fed will do it?

But the simple fiscal theory models in this book are kinder to the Fed. The Fed could tamp down inflation by swiftly raising rates, and exploiting whatever mechanism lies behind a negative short-run effect. And we have seen that rate rises are useful to smooth fiscal shocks, producing slow steady inflation rather than sharp price-level jumps. But the emphasis on a greater than one-for-one response, and the view that failing to promptly follow that policy will lead to instability is gone.

Indeed, if the rational expectations versions of the models in this book are right, inflation is stable under an interest rate target. If the Fed left the interest rate alone, inflation would eventually return, though transitory may take a long time and involve a lot of short-run dynamics on the way. All the hedgeing of Section 5.3 still applies. The Fed would have to say this is its strategy, which it certainly does not do, and stick with it while short-run dynamics and fiscal shocks run their course. If people think that after a certain amount of inflation the Fed will give in and raise rates, then inflation will start up in advance and the strategy would fall apart. Still, history may be kind to the Fed and suggest that it worked its way to such a strategy by “as-if” experience-based action, even though the Fed’s models and theories say otherwise.

Suppose inflation does surge in the 2020s. What will it take to stop it? The traditional view demands a sustained period of high real interest rates. If expectations are adaptive or mechanistic, that period of real interest rates must cause a fairly deep recession.

The fiscal theory plus rational expectations view offers more possibilities. A period of high real interest rates will likely be the policy choice, using whatever the short-run negative response is to quickly push inflation down, and then nominal rates can quickly fall to the new lower expected inflation. Whether it works, and how much recession is involved depends on that mechanism. The long-term debt mechanism we have explored requires that the higher rates are unexpected and credibly long-lasting. But financial friction or other mechanisms may have other preconditions, and we will learn what those mechanisms are.

The model, and Sargent’s timeless analysis of the ends of inflations, opens another possibility: A credible joint fiscal, monetary, and microeconomic reform, can allow a relatively painless disinflation, and one in which nominal interest rates fall immediately in Fisherian fashion.

Which of these will happen? A repeat of 1980 will be harder this time. Most obviously, the willingness of our government to sustain a deliberate, bruising and persistent recession, with monetary stringency rather than the monetary largesse of 2008 and 2020, seems much weaker. However, a decade of inflation may change that, as it did in the 1970s.

But no matter which theory applies, fiscal policy will place a greater constraint on monetary policy based on high real interest rates. In 1980, the debt-to-GDP ratio was 25%. In 2021 it is 100%, and rising swiftly. If our government wishes to repeat 1980, it will first of all have to pay four times larger real interest costs on the debt. 5% real interest rates mean 5% of GDP additional deficit, $1 trillion 2021 dollars, for each year that the real interest rates continue. That amount must be paid by higher primary surpluses, immediately or credibly in the future. Will our government do it? The last time debt-to-GDP was 100%, in the aftermath of WWII, the government explicitly told the Federal Reserve to hold interest rates down to help finance the debt.

Second, the government will have to raise surpluses further, to pay a windfall to long-term bondholders, as it did in the 1980s. People who bought 10-year Treasury bonds in September of 1981 got a 15.84% yield, as markets expected inflation to continue. From September 1981 to September 1991, the CPI grew at a 3.9% average rate. By this back-of-the-envelope calculation, those bondholders got a 12% annual real return. That return came courtesy of U.S. taxpayers, though largely through growth and a larger tax base rather than higher tax rates. This effect is now four times larger as well.

Finally, but largest of all, this time the underlying problem will likely be more clearly fiscal. The U.S. government will have to solve the long-run fiscal problem and convince bondholders once again that the U.S. repays its debt.

Without the fiscal backing, the monetary stabilization will fail, and that applies to all our theories. In a fiscally-driven inflation, it can happen that the central bank raises rates to fight the inflation, that raises the deficit via interest costs, and only makes inflation worse. This has, for example, been an analysis of several episodes in Brazil. The simulations of Section17.4.2 make this point explicitly.

But the chance of any such large fiscal contraction, a thoroughgoing fiscal reform, seems remote in current U.S. politics. Anchoring of expectations from the belief that this will all happen smoothly seems doubtful.

A successful inflation stabilization always combines fiscal, monetary, and microeconomic reform, in a durable new regime that commits to pay its debts. 1980 was such an event, not just a period of high interest rates. High interest rates can drive down inflation temporarily in all these models, giving time for the fiscal (1986 tax reform) and microeconomic reforms to take effect. In their absence, inflation takes off again. A new inflation stabilization would have to be such an event as well, but in the face of at least four times larger debts, larger structural deficits, and a more deeply entrenched regulatory regime.

Or, inflation may fade away and all this speculation will apply to 2040 or 2050.

[ad_2]