[ad_1]

Subscribe

Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon

Castbox | Stitcher | Podcast Republic | RSS | Patreon

Podcast Transcript

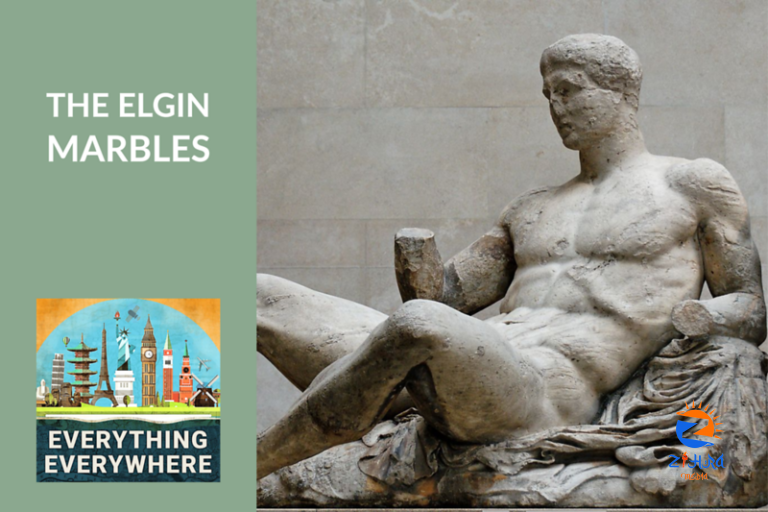

Beginning in 1801, the British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, the Earl of Elgin, began a project to document the sculptures located at the Parthenon in Athens.

He then took it one step further and took half of the sculptures at the Parthenon and shipped them back to England.

It has been a source of controversy and diplomatic conflict ever since.

Learn more about the Elgin Marbles, and how the greatest artistic works of Greece ended up in London, on this episode of Everything Everywhere Daily.

This episode is sponsored by the Tourist Office of Spain.

The dish that is most associated with Spain is paella. It is a rice dish that hails from the region of Valencia and goes back centuries.

If you are a lover of paella, you are in luck because September 20th is World Paella Day.

It is a great time to experience Spain’s most famous dish. There are recipes for making your own paella on the visitvalencia.com website. You can also visit a Spanish restaurant in your area to enjoy some classical paella.

And of course, if you can swing it, you have to make your way to Valencia, the home of paella. There you can experience all the different varieties of which are available.

You can learn more about paella and visiting Valencia at Spain.info.

Once again, that is Spain.info.

Greece in the early 19th century wasn’t yet an independent country. It had been under the rule of the Ottoman Empire since the mid 15th century, and this was the geopolitical situation in Athens in 1801.

Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin was appointed as the Ambassador Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary of His Britannic Majesty to the Sublime Porte of Selim III, Sultan of Turkey.

Prior to arriving in the Ottoman Empire, he asked the British government if they were interested in hiring artists to make drawings and take plaster casts of the sculptures at the Parthenon.

The British government was in no way interested.

However, even if the government wasn’t interested, Thomas Bruce still was.

So, using his own funds, he hired a team of artists to document the artwork at the Parthenon.

So, far, all of his plans for documenting what was at the Parthenon were perfectly fine. If he had just stuck to this, I’d probably be doing an episode about something else right now.

However, he didn’t just stick to documenting the artwork. He soon began removing whatever sculptures that he could.

In total, he took 21 full statues, 15 metope panels, which are carved rectangular architectural pieces, and a full 75 meters of the Parthenon frieze which decorated the upper interior of the Parthenon.

All of this marble sculpture was sent to Malta, and then to England. They became known as the Elgin Marbles, named after Earl of Elgin, and because they are all made out of marble. They are also known as the Parthenon Marbles.

This was all done at the personal expense of the earl at a cost of £74,240, or what today would be worth about £5,000,000 or $6.8 million dollars.

His original plan was simple to decorate his home in England.

While the artwork is interesting in itself, that really isn’t what the story of the Elgin Marbles is about.

Almost immediately after the art was delivered to London, there was controversy. Many of the elite in London came to see the marbles and they were considered a hit.

However, some people like Lord Byron denounced the removal of the art from Greece and considered Elgin to be a vandal. He mentioned the removal of the marbles in his 1812 poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage.

Sir John Newport was another member of the aristocracy who objected to the absconding of the marbles. He wrote:

The Honourable Lord has taken advantage of the most unjustifiable means and has committed the most flagrant pillages. It was, it seems, fatal that a representative of our country loot those objects that the Turks and other barbarians had considered sacred.

There was a debate in parliament on the marbles and there was a vote stating that the marbles had been given asylum in a free country, and the parliament in 1816 voted to purchases the marbles.

Elgin sold them to the government at half the price it cost him because he had to cover debts from a divorce. He was actually offered a higher price by Napoleon to bring them to France and put them in the Louvre, but they wanted them to remain in Britain.

From there, the marbles were given to the British Museum where they reside today.

The controversy about the marbles never went away. In 1832, Greece finally became independent from the Ottoman Empire. One of the first things they did was establish a program of monument protection and they tried to repatriate artifacts that have been taken out of their country.

The new Greek government claimed that the marbles were stolen illegally.

This began a series of legal maneuvers on behalf of the British to justify keeping the marbles.

At the time the marbles were removed from the Parthenon, it was a Turkish military base. Elgin couldn’t just waltz up to the Parthenon and do whatever he wanted.

To do so, he needed official approval from the sultan and that came in the form of a document called a firmen.

Elgin produced an English translation of an Italian copy of the firmen, and this is what the legal argument of the British rests on.

You can say what you want about the efficiency and the corruption of the Ottoman Empire, but they were really good at paperwork.

The original version of the firmen in Turkish has never been found in the Ottoman records.

As such, the authenticity of the firmen has been called into question.

There have been many legal opinions written about the legal status of the marbles. They have included arguments such that the firmen was forged, and that the firmen, even if it was legitimate, didn’t include the removal of any of the pieces of art. It only included the authority to take drawings and molds.

There is a lot written about the legal legitimacy of the firmen and I could talk about it, but at the end of the day, none of it matters because there is an even more important legal theory that takes precedence. It is known as “finders keeper, losers weepers”.

Even though Greece has been talking about getting the marbles back for almost 200 years, modern efforts to get the marbles returned only began in the 1980s.

In 1981 the International Organising Committee – Australia – for the Restitution of the Parthenon Marbles was established, and in 1983 the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles was formed.

In 1983, the first formal request by the Greek government to the British Museum was made for the return of the marbles.

One of the first excuses used by the British Museum was that there wasn’t a place in at the Parthenon to properly show the marbles.

In response, the Greek government built the Acropolis Museum and built a brand new state-of-the-art space for the marbles to be put on display. After it was built, the Greeks said, “OK. We got the space built. Can we have the marbles back now?”, and the British Museum said, “Uhhhh, no”.

UNESCO offered to mediate a solution, and the British said that UNESCO isn’t an institution that governments museums, so they wouldn’t be the proper organization to do this.

The International Association for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures was founded in 2005. It has gotten support from celebrities like George Clooney and Matt Damon, who were both in the movie Monument Men, which was about a unit in World War II that found stolen Nazi art.

The current room where the marbles are located in the British Museum, the Duveen Gallery, is arguably much worse than the new facility built in Athens. There is no climate control and the skylight in the room is leaking.

Successive British governments have taken the position that the marbles will remain in Britain and will not be returned. Most recently, Prime Minister Boris Johnson has reiterated this in March of 2021.

The British public however doesn’t seem to agree. Almost every poll taken over the last 20 years shows public support for returning the marbles. In 2014, a poll showed 40% of the British public was in support of returning the marbles whereas only 15% wanted them to remain.

There are some noted scholars who think that the marbles should remain in London. Their argument is that they have been better protected in London than they would have been in Athens over the last 200 years and that they have been accessible to more people than they would otherwise have been if they were in Athens.

The Elgin Marbles are only the most notable works of art taken from their original countries. Countless works of art from places such as Egypt, China, and Mexico have found their way to museums in Europe, mostly taken in the 18th and 19th centuries.

I personally think that some or all of the marbles will eventually be returned to Greece at some point. It is really just a matter of when, and how many of them will be returned.

Claims of preservation and safety no longer apply to the new Acropolis Museum. Moreover, the Acropolis Museum has offered to do an exchange of other artifacts with the British Museum and to put some of the marbles on loan to other museums, so I’m guessing at some point a deal with probably be struck.

Until that time, you can view the marbles for yourself. The next time you find yourself in London you can visit the British Museum free of charge to gaze upon the marbles that once adorned the Parthenon.

[ad_2]