[ad_1]

Subscribe

Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon

Castbox | Stitcher | Podcast Republic | RSS | Patreon

Podcast Transcript

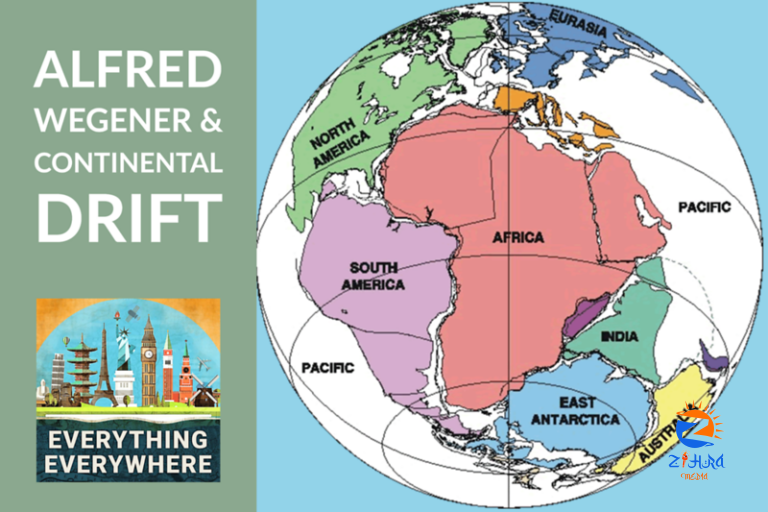

In 1910, a German Earth scientist noticed something about the map of the world. South America seemed to fit into Africa. North America seemed to fit into northwest Africa and Europe.

He proposed that the continents may at one time have been joined and subsequently moved.

The scientific community laughed at him and rejected his idea.

Learn more about Alfred Wegener and the theory of Continental Drift, on this episode of Everything Everywhere Daily.

This episode is sponsored by Brilliant.org

Brilliant’s mission is to inspire and develop people to achieve their goals in STEM — one person, one question, and one small commitment to learning at a time.

They enable great teachers to illuminate the soul of math, science, and engineering through bite-sized, interactive learning experiences. Their courses explore the laws that shape our world, elevating math and science from something to be feared to a delightful experience of guided discovery.

If you are interested in learning more about any STEM subject go to everything-everywhere.com/brilliant

Once again, that is everything-everywhere.com/brilliant

Alfred Wegener was a really interesting man. Born in 1880 in Germany, he got his degree in astronomy but became a meteorologist, which was still a rather new field at the time.

His primary interest was in the northern polar region and how air circulated in that region.

He participated in four expeditions to Greenland and was one of the first meteorologists to adopt the use of weather balloons.

However, meteorology and expeditions to Greenland aren’t what Alfred Wegener is best known for. It is for his contributions to geology and geophysics.

The idea that he is remembered for began innocently enough on Christmas Day 1910. He was at his friend’s house when he was looking at his new world atlas.

He made the observation that South American and Africa seemed like they fit together like puzzle pieces.

I should note that he was far from the first person to notice this. Once decent maps began being published in the last part of the 16th century, people first observed the same thing.

The first person we know of who made the observation was Dutch cartographer, Abraham Ortelius. Ortelius created the first modern atlas in 1570, which means he probably was the first person to have the idea because no one before that really had a good grasp of the geography of the continents.

William Kious wrote in his book on geologic history:

Abraham Ortelius in his work Thesaurus Geographicus … suggested that the Americas were “torn away from Europe and Africa … by earthquakes and floods” and went on to say: “The vestiges of the rupture reveal themselves, if someone brings forward a map of the world and considers carefully the coasts of the three [continents].”

Ortelius was far from alone. After him, the idea that the continents fit together somehow kept popping up. Theodor Christoph Lilienthal, Alexander von Humboldt. Antonio Snider-Pellegrini, and Alfred Russel Wallace all made the same observation one to two hundred centuries before.

Moreover, there were several other scientists just a decade before who came to a similar conclusion.

In fact, there is a good chance that you have probably made the same observation one of the first times you saw a world map.

Wegener took the idea to another level. He began by cutting up maps and piecing the landmasses together like a puzzle. He was able to put the continents together into one giant continent that he named “Pangea”, from the Greek words for all and land.

I should note that Wegener wasn’t just piecing together the land that we can see today, but the continental shelves, which actually fit much better. This would sea levels about 200 meters lower than what it is today.

However, this wasn’t just a physical puzzle. Shapes could sort of fit together by coincidence. The fact that something is convex and something else is concave, doesn’t prove that they were once connected.

Wegener then began looking for more lines of evidence, and he found lots of them.

Animals would oftentimes be similar on different continents. Marsupials in Australia looked like marsupials in South America. Moreover, the tapeworms which infected the animals on both sides were similar.

Likewise, he noted similarities in plant species as well.

Layered geological formations ended on one continent and then restarted again on another continent. The Appalachian Mountains in North America are similar to mountains found in Greenland, Ireland, Britain, and Norway.

And perhaps most importantly, the location of certain fossils could be found across continents. For example, mesosaurus fossils, which is a small freshwater crocodile, can only be found in Brazil and South Africa. It was inconceivable that a small reptile could cross the ocean.

A land reptile called a Lystrosaurus was found in similar rocks in Africa, India, and Antarctica.

What separated Wegener’s theory from those who came before him was how thorough he assembled his evidence.

He presented his theory for the first time on January 6, 1912, to the German Geological Association and he initially called his theory “continental displacement”.

The records from the meeting note that there was no discussion after his presentation.

In 1915, he published a book in German titled The Origin of Continents and Oceans. By that time, the First World War was in full swing and geology took a back seat. There was little discussion about Wegener’s theory for the next several years. It was during this time that Wegener began using the term “continental drift”.

However, in 1922 his book was translated into English, and then the word of geology exploded.

Almost the entire geology community worldwide came out to denounce Wegener.

Much of this was a latent anti-German sentiment that was leftover from the war. American and British geologists were especially harsh. However, German geologists joined in as well.

Another factor behind the vitriol was the fact that Wegener wasn’t a geologist by training. He was a meteorologist and an astronomer. He wasn’t staying in his lane, and it upset the sensibilities of geologists.

Wegener’s theory was called many things including “moving crust disease”, “wandering pole plague”, and “Germanic pseudo-science”. He was personally accused of having “delirious ravings” and of “toying with the evidence to spin himself into “a state of auto-intoxication.”

Roland Chamberlain of the University of Chicago noted “If we are to believe Wegener’s hypothesis we must forget everything which has been learned in the last 70 years and start all over again.”

Many leading geologists basically told their students that a belief in moving continents was sure way to quickly sink their career.

To be fair, there were some serious problems with Wegener’s theory.

First, his proposed rate of movement of the continents was way too fast. He thought they moved at 250 centimeters a year. Based on current measurements, his estimate was a hundred times too fast.

Second, he didn’t offer up any explanation for how and why the continents moved. There would need to be some incredible force to move entire continents. Without this explanation, it was a very hard theory for most geologists to accept.

Wegener died in 1930 in Greenland while on a relief mission to bring food to a camp.

After his death, his theory was mostly forgotten, and if it was mentioned it was done so to denounce it.

However, starting in the 1950s, something started to happen. More evidence starting coming in, and it seemed to vindicate Wegener.

The discovery of paleomagnetism on the ocean floor provided strong evidence that the continents were moving. The rock on the seafloor has a magnetic orientation which is baked into the rock when it is formed. What was found was alternating orientations, indicating that there was new rocking being formed as the plates spread, and as the magnetic poles shifted.

Most importantly, a mechanism was found which explained how the continents moved. It was called plate tectonics.

Plate tectonics was the rosetta stone for understanding all geology. It explained why the continents moved, it explained earthquakes and volcanoes, and island chains.

Plate tectonics understood the world as being covered by plates. Some of them were oceanic crust and some were continental crust. They were all moving slowly due to convections within the Earth’s mantle. Some plates spread apart, like Europe and North America.

Some plates subduct under other plates like what is happened to the Pacific Ocean and Japan. Others pass each other like two bricks rubbing against each other, which is what happens at the San Andres fault.

In the end, Alfred Wegener was right….sort of. His initial theory as he proposed it wasn’t really correct and the term “continental drift” is no longer used today. However, his larger point about the continents moving was confirmed and is universally accepted by geologists today.

Even if Wegener wasn’t totally right, his critics were totally wrong.

The story of Alfred Wegener is a textbook example of the difficulty of accepting new scientific ideas.

Wegener’s experience provides proof to what the Nobel Prize winning physicist Max Plank said:

A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it. . .

Or as it is more commonly phrased, science advances one funeral at a time.

[ad_2]